Paracas culture

Area of development and influence of the Paracas culture. | |

| Period | Early Horizon |

|---|---|

| Dates | c. 800 BCE – 100 BCE |

| Major sites | Paracas Candelabra |

| Followed by | Nazca culture |

The Paracas culture was an Andean society existing between approximately 800 BCE and 100 BCE, with an extensive knowledge of irrigation and water management and that made significant contributions in the textile arts. It was located in what today is the Ica Region of Peru. Most information about the lives of the Paracas people comes from excavations at the large seaside Paracas site on the Paracas Peninsula, first formally investigated in the 1920s by Peruvian archaeologist Julio Tello.

The Paracas Cavernas are shaft tombs set into the top of Cerro Colorado, each containing multiple burials. There is evidence that over the centuries when the culture thrived, these tombs were reused. In some cases, the heads of the deceased were taken out, apparently for rituals, and later reburied. The associated ceramics include incised polychrome, "negative" resist decoration, and other wares of the Paracas tradition. The associated textiles include many complex weave structures, as well as elaborate plaiting and knotting techniques.

The necropolis of Wari Kayan consisted of two clusters of hundreds of burials set closely together inside and around abandoned buildings on the steep north slope of Cerro Colorado. The associated ceramics are very fine plain wares, some with white and red slips, others with pattern-burnished decoration, and other wares of the Topara tradition. Each burial consisted of a conical textile-wrapped bundle, most containing a seated individual facing north across the bay of Paracas, next to grave offerings such as ceramics, foodstuffs, baskets, and weapons. Each body was bound with cord to hold it in a seated position, before being wrapped in many layers of intricate, ornate, and finely woven textiles. The Paracas Necropolis textiles and embroideries are considered to be some of the finest ever produced by Pre-Columbian Andean societies. They are the primary works of art by which Paracas culture is known. Burials at the necropolis of Wari Kayan continued until approximately 250 CE. Many of the mortuary bundles include textiles similar to those of the early Nazca culture, which arose after the Paracas.

Political and Social Organization[edit]

Paracas lacked a central figurehead or government, and were instead comprised of local chiefdoms.[2] These communities were joined by shared religion and trade, but maintained economic and political autonomy.[3][4] Early Paracas communities were within the Chavín sphere of interaction and formed their own versions of the cult.[4] In the middle period (500–380 BCE) Chavín's influence on the Paracas culture dwindled and communities began to form their own unique identities.[4] Relationships between these chiefdoms were not always peaceful, as evidence by violent battle wounds, trophy heads, and obsidian knives found at Paracas sites.[2]

Subregions within the larger Paracas sphere emerged from local integration, including the Chinca Valley, the Ica Valley, and the Palpa Valley.[3] The Chinca Valley was likely the political center of Paracas culture, with the Paracas Peninsula possibly acting primarily as burial grounds and Ica being a peripheral zone of Chincha.[5][3] Chincha has numerous roads, geoglyphs, and religious centers that would have served as a ritual meeting point.[3] Large mounds were built for ceremonial purposes throughout the valley, and there is little evidence for permanent occupation at these sites; instead, agriculture and fishing occurred in the land surrounding mounds and ritual complexes.[5] People would have come from both coastal and highland communities, allowing for social and political integration as well as economic exchange.[3] Large mounds were built for ceremonial purposes throughout the valley, and there is little evidence for permanent occupation at these sites; instead, agriculture and fishing occurred in the land surrounding mounds and ritual complexes.[5] The valley has extensive irrigation systems to increase agricultural production, a trait found throughout Paracas settlements and monumental sites.[4]

The site Cerro del Gentil in the Upper Chincha Valley dates to approximately 550-200 BCE and was used to host feasts for people throughout the Paracas sphere of influence.[5] [6]Though one of the smaller sites in the valley, it has still been subject to intensive research and is useful for understanding the political evolution of Paracas. The site is composed of a monumental platform mound with two sunken courts surrounded by agricultural fields.[6] Strontium isotope testing of offerings at the site shows that people came from long distances to feast, suggesting that distant alliances were built initially and intentionally rather than consolidating local alliances first.[6] A termination ritual occurred at the site around 200 BCE, in which large amounts of pottery, baskets, and other offerings were made along with a large feast.[5] The high variability of offerings at the site, including bird feathers from far northern Peru, again show the variety of individuals using the site.[5]

Decline and the Paracas/Nazca Transition[edit]

Nazca Culture and iconography are believed by scholars such as Helaine Silverman to have evolved from Paracas culture.[7][2] Nasca had shared religion with the Paracas, and continued the traditions of textile making, head-hunting, and warfare in early phases.[2] Hendrik Van Gijseghem notes that Paracas remains in the Río Grande de Nazca drainage, the heartland of Nazca culture, are limited.[8] In contrast, there are abundant Paracas remains in the Ica, Pisco, and Chincha valleys, as well as the Bahía de la Independencia.[8] He noted that the southern Nazca region, which became the most populous region of its culture, was never an important area of Paracas occupation.[8] He believes that initial settlement of the region by Paracas populations and subsequent population growth mark the beginning of Nazca society.[8]

Many Paracas sites were later inhabited by the Topará tradition, and the decline of the Paracas culture is often thought to be associated with the "invasion" of the Topará culture the north at approximately 150 BCE.[9][2] This is largely based on Topará-stlye ceramics found at late Paracas and initial Nazca sites.[9] However, this theory has recently been called into question; the termination ritual at Cerro del Gentil and other Chincha Valley sites precedes any Topará occupation, and the sites show no sign of resistance to an invading culture.[10][11] Radiocarbon dates show that the earliest accepted Topará site, Jahuay, was first occupied ~165 years after the closure of Cerro del Gentil.[10] This suggests that the decline of Paracas and the Paracas-Nazca transition was already underway when the Topará tradition emerged.

Paracas mummy bundles[edit]

The dry environment of southern Peru's Pacific coast allows organic materials to be preserved when buried.[12] Mummified human remains were found in a tomb in the Paracas peninsula of Peru, buried under layers of cloth textiles.[13] The dead were wrapped in layers of cloth called "mummy bundles". These bodies were found at the Great Paracas Necropolis along the south Pacific coast of the Andes.[14] At the Necropolis there were two large clusters of crowded pit tombs, totaling about 420 bodies, dating to around 300–200 BCE.[15] The mummified bodies in each tomb were wrapped in textiles.[7] The textiles would have required many hours of work as the plain wrappings were very large and the clothing was finely woven and embroidered. The larger mummy bundles had many layers of bright colored garments and headdresses.[13][16] Sheet gold and shell bead jewelry was worn by both men and women, and some were tattooed.[17] The shape of these mummy bundles has been compared to a seed, or a human head.[12]

According to Anne Paul, this shape could have been a conscious choice by the people, with the seed a symbol of rebirth.[13][16] Paul also suggests that the detail and high quality of the textiles found in the mummy bundles show that these fabrics were used for important ceremonial purposes.[12][16] Both native Andean cotton and the hair of camelids like the wild vicuña and domestic llama or alpaca come in many natural colors. Yarns were also dyed in a wide range of hues, used together in loom weaving and many other techniques. This combination of materials shows trading relationships with other communities at lower and higher elevations.[16]

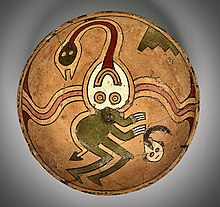

The imagery found on these textiles included ceremonial practices.[18] Some depicted a fallen figure, or possibly flying. Some figures appear to have face paint, and hold a severed head, also called trophy heads.[18] Victims' heads were severed and collected during battles or raids.[13] Possibly, the head of a person was considered their life force, the place in the body where the spirit was located.[18] Not only did these textiles show important symbols of the Paracas cosmology, it is thought that they were worn to establish gender, social standing, authority, and indicate the community in which one resided.[17]

Different color schemes characterize the textiles of Paracas Cavernas, early Paracas Necropolis and later Nazca-related styles. [19] The dyes used came from many regions of the Andes and are an example of reciprocity, as people from different altitudes traded with one another for different goods.[18] The color red comes from the cochineal bug found on the prickly pear cactus.[20] The cochineal was ground up with mortar and pestle to create a red pigment.[20] Yellow dyes could be made from the qolle tree and quico flowers, while orange dyes can be extracted from a type of moss called beard lichen.[20] For the color green the most common plant used is the cg'illca, mixed with a mineral called collpa.[20] While blues are created from a tara, the deeper a hue of blue, the more the mineral collpa was added.[20] The process of creating dyes could take up to several hours. Then it could take another two hours for women to boil and dye the fibers.[20] This work was followed by spinning and weaving the fibers.

The woven textiles of Paracas were made on backstrap looms generally in solid color. These webs were richly ornamented with embroidery in two different styles. The earlier linear style embroidery was done in running stitches closely following the furrows of the weaving itself. Red, green, gold and blue color was used to delineate nested animal figures, which emerge from the background with upturned mouths, while the stitching creates the negative space. These embroideries are highly abstracted and difficult to interpret.[21] The later used Block-color style embroidery was made with stem stitches outlining and solidly filling curvilinear figures in a large variety of vivid colors. The therianthropomorphic figures are illustrated with great detail with systematically varied coloring. [22]

The textiles and jewelry in the tombs and mummy bundles attracted looters.[15] Once discovered, the Paracas Necropolis was looted heavily between the years 1931 and 1933, during the Great Depression, particularly in the Wari Kayan section.[23] The amount of stolen materials is not known; however, Paracas textiles began to appear on the international market in the following years.[23] It is believed the majority of Paracas textiles outside of the Andes were smuggled out of Peru.[23]

Due to a lack of laws to preserve artifacts and against smuggling, thefts continued to increase, particularly of South American artifacts.[23] In 1970 UNESCO created the Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property.[24]

Cranial Modification[edit]

Artificial Cranial Deformation[edit]

Like many ancient Andean societies, the Paracas culture participated in artificial cranial deformation. Of the excavated and accessible skulls from the Paracas Cavernas, the vast majority of skulls were visibly modified. The skulls were observed to be primarily of two shapes: Tabular Erect or Bilobate.[25] Though Tabular Erect was the most common among both sexes, Bilobate skulls were observed at a much higher rate in female skulls.[25] This association with sex has evidence in some Paracas ceramics, where men and women are depicted with distinctly Tabular Erect and Bilobate heads, respectively.[25]

Some archaeologists suggest that Andean conceptions of gender and cosmovision could support a quadripartite (masculine–masculine, masculine–feminine, feminine–masculine and feminine–feminine) construction of gender that could explain the decisions of alteration type per sex.[25] Cranial modification shape appears not to be tied to social status (based on burial goods), or kinship (based on groupings of remains).[25]

Trepanation[edit]

The Paracas culture also shows evidence of the earliest trepanations in the Americas, using lithic scraping and drilling techniques to remove sections of the skull. The likely motivation for trepanation may have been to treat the depressed skull fractures that are commonly observed in Paracas culture remains, likely caused by the slings, clubs, and atlatls commonly found in mummy bundles along the south Peruvian coast.[26]: 116–122 However, many of the Paracas trepanations remove such a large amount of the skull that direct evidence of skull fractures or similar injuries coinciding with trepanation is elusive. Observed trepanations and skull fractures are both most common on the front of the skull, lending indirect support to an association between the two.

Based on the level of bone reaction and healing observed in a trepanned skull, archaeologists can estimate the survival rate of these medical procedures: 39% of patients would have died during trepanation or shortly after (with no bone reaction being observed), and nearly 40% of patients would have survived long-term (with extensive bone reaction being observed).[26]: 113 Currently, the best estimate of the frequency of trepanations in the Paracas culture is around 40%, though sampling bias in the initial selection of skulls, the large quantity of unopened mummy bundles, and the 39% mortality rate of Paracas trepanation make an estimate this high very unlikely.[26]: 133–134

Paracas geoglyphs[edit]

In 2018 RPAS drones used by archaeologists to survey cultural evidence revealed many geoglyphs in Palpa province. These are being assigned to the Paracas culture. Many have been shown to predate the associated Nazca lines by a thousand years. In addition, some show a significant difference in subjects and locations, for instance, being constructed on a hillside rather than the desert valley floor.[27] Additional research is being conducted on these geoglyphs.

References[edit]

- ^ Bottle, Feline Face, 4th–3rd century BCE Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ^ a b c d e Proulx, Donald A. (2008), Silverman, Helaine; Isbell, William H. (eds.), "Paracas and Nasca: Regional Cultures on the South Coast of Peru", The Handbook of South American Archaeology, New York, NY: Springer, pp. 563–585, doi:10.1007/978-0-387-74907-5_29, ISBN 978-0-387-74907-5, retrieved 2024-05-22

- ^ a b c d e Osborn, Jo; Hundman, Brittany; Weinberg, Camille; Huaman, Richard Espino (August 2023). "REASSESSING THE CHRONOLOGY OF TOPARÁ EMERGENCE AND PARACAS DECLINE ON THE PERUVIAN SOUTH COAST: A BAYESIAN APPROACH". Radiocarbon. 65 (4): 930–952. Bibcode:2023Radcb..65..930O. doi:10.1017/RDC.2023.67. ISSN 0033-8222.

- ^ a b c d Tantaleán, Henry (2021-09-29), "The Paracas Society of Prehispanic Peru", Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Latin American History, doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199366439.013.981, ISBN 978-0-19-936643-9, retrieved 2024-05-23

- ^ a b c d e f Tantaleán, Henry; Stanish, Charles; Rodríguez, Alexis; Pérez, Kelita (2016-05-04). "The Final Days of Paracas in Cerro del Gentil, Chincha Valley, Peru". PLOS ONE. 11 (5): e0153465. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1153465T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0153465. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4856392. PMID 27144824.

- ^ a b c Stanish, Charles; Tantaleán, Henry; Knudson, Kelly (2018). "Feasting and the evolution of cooperative social organizations circa 2300 B.P. in Paracas culture, southern Peru". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 115 (29): E6716–E6721. Bibcode:2018PNAS..115E6716S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1806632115. ISSN 0027-8424. JSTOR 26510998. PMC 6055157. PMID 29967147.

- ^ a b Silverman, Helaine (December 1994). "Paracas in Nazca: New Data on the Early Horizon Occupation of the Rio Grande de Nazca Drainage, Peru". Latin American Antiquity. 5 (4): 359–382. doi:10.2307/971822. JSTOR 971822. S2CID 130499340.

- ^ a b c d Van Gijseghem, Hendrik (December 2006). "A Frontier Perspective on Paracas Society and Nasca Ethnogenesis". Latin American Antiquity. 17 (4): 419–444. doi:10.2307/25063066. JSTOR 25063066. S2CID 163587059.

- ^ a b Osborn, Jo; Hundman, Brittany; Weinberg, Camille; Huaman, Richard Espino (August 2023). "REASSESSING THE CHRONOLOGY OF TOPARÁ EMERGENCE AND PARACAS DECLINE ON THE PERUVIAN SOUTH COAST: A BAYESIAN APPROACH". Radiocarbon. 65 (4): 930–952. Bibcode:2023Radcb..65..930O. doi:10.1017/RDC.2023.67. ISSN 0033-8222.

- ^ a b Osborn, Jo; Hundman, Brittany; Weinberg, Camille; Huaman, Richard Espino (August 2023). "REASSESSING THE CHRONOLOGY OF TOPARÁ EMERGENCE AND PARACAS DECLINE ON THE PERUVIAN SOUTH COAST: A BAYESIAN APPROACH". Radiocarbon. 65 (4): 930–952. Bibcode:2023Radcb..65..930O. doi:10.1017/RDC.2023.67. ISSN 0033-8222.

- ^ Tantaleán, Henry; Stanish, Charles; Rodríguez, Alexis; Pérez, Kelita (2016-05-04). "The Final Days of Paracas in Cerro del Gentil, Chincha Valley, Peru". PLOS ONE. 11 (5): e0153465. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1153465T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0153465. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4856392. PMID 27144824.

- ^ a b c Paul, Anne (1991). Paracas Art and Architecture: Object and Context in Southern Coastal Peru. University of Iowa Press. pp. 678–679. ISBN 978-0877453277.

- ^ a b c d Wallace, Dwight T. (1960). "Early Paracas Textile Techniques". American Antiquity. 26 (2): 279–281. doi:10.2307/276210. ISSN 1045-6635. JSTOR 276210. S2CID 163918945.

- ^ Paul, Anne (1990). Paracas Ritual Attire: Symbols of Authority in Ancient Peru. The Civilization of the American Indian Series. The University of Oklahoma. pp. 290–292. ISBN 978-0806122304.

- ^ a b Proulx, Donald A. (2008), "Paracas and Nasca: Regional Cultures on the South Coast of Peru", The Handbook of South American Archaeology, Springer New York, pp. 563–585, doi:10.1007/978-0-387-74907-5_29, ISBN 978-0387749068

- ^ a b c d Paul, Anne (1990). Paracas Ritual Attire: Symbols of Authority in Ancient Peru. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0806122304. OCLC 925134619.

- ^ a b Peters, Ann H.; Tomasto-Cagigao, Elsa (2017), "Masculinities and Femininities: Forms and Expressions of Power in the Paracas Necropolis", Dressing the Part: Power, Dress and Representation in the Pre-Columbian Americas, University Press of Florida, pp. 371–449, ISBN 9780813062211

- ^ a b c d Stone, Rebecca (2012). Art of the Andes: From Chavin to Inca. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0500204153. OCLC 792747356.

- ^ Peters, Ann H. (2016), "Emblematic and Material Color in the Paracas-Nasca Transition", Nuevo Mundo - Mundos Nuevos, Colloques: Textiles amérindiens. Regards croisés sur les couleurs, doi:10.4000/nuevomundo.69877

- ^ a b c d e f de Mayolo, Kay K. Antúnez (April 1989). "Peruvian Natural Dye Plants". Economic Botany. 43 (2): 181–191. doi:10.1007/BF02859858. S2CID 7091754.

- ^ Stone, Rebecca (2012). Art of the Andes from Chavin to Inca (3 ed.). Thames Hudson. pp. 63–67.

- ^ Stone, Rebecca (2012). Art of the Andes from Chavin to Inca (3 ed.). Thames Hudson. p. 68.

- ^ a b c d Bird, Junius B. The Junius B. Bird Pre-Columbian Textile Conference, 1973, Washington D.C., May 19 & 20, 1973: abstracts of papers with illustrative slides. OCLC 46447979.

- ^ "1970 Convention | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization". unesco.org. 2017. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Gómez-Mejía, Juliana; Aponte, Delia; Pezo-Lanfranco, Luis; Eggers, Sabine (February 2022). "Intentional cranial modification as a marker of identity in Paracas Cavernas, South-Central Coast of Peru". Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. 41: 103264. Bibcode:2022JArSR..41j3264G. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2021.103264. ISSN 2352-409X.

- ^ a b c Verano, John W. (2016). Holes in the head: the art and archaeology of trepanation in ancient Peru. Studies in pre-Columbian art and archaeology. Washington, D.C: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. ISBN 978-0-88402-412-5.

- ^ Greshko, Michael, "Exclusive: Massive Ancient Drawings Found in Peruvian Desert", National Geographic, 05 April 2018

Further reading[edit]

- Paracas Art and Architecture: Object and Context in South Coastal Peru by Anne Paul, Publisher: University of Iowa Press, 1991 ISBN 0-87745-327-6

- Ancient Peruvian Textiles by Ferdinand Anton, Publisher: Thames & Hudson, 1987, ISBN 0-500-01402-7

- Textile art of Peru by Jose Antoni Lavalle, Publisher: Textil Piura in the Textile (1989), ASIN B0021VU4DO

External links[edit]

- CIOA Field Report of a Paracas-period Site

- Paracas Textiles at the Brooklyn Museum

- Gallery of Paracas objects (archived link, text in Spanish)

- Impacts on Tourism at Paracas (in Spanish)

- Precolumbian textiles at MNAAHP (in Spanish)

- Paracas textile at the British Museum

- Ancient Peruvian ceramics: the Nathan Cummings collection by Alan R. Sawyer, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Paracas culture (see index)