Historias del Kronen (novel)

| Author | José Ángel Mañas |

|---|---|

| Country | Spain |

| Language | Spanish |

| Series | Kronen Tetralogy |

| Genre | Novel |

| Published | 1994 |

| Publisher | Ediciones Destino |

| ISBN | 842332351X |

| Followed by | Mensaka (1995) |

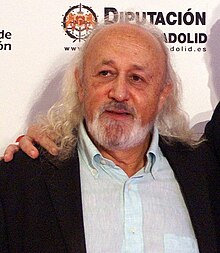

Historias del Kronen is the first novel by Madrid-born Spanish author José Ángel Mañas, with which he was a finalist for the Premio Nadal in January 1994.[1][2] Published by Spanish publishing house Ediciones Destino in 1994[3]—when the author was only 23 years old,[4] and which he claims he wrote in only 15 days[5]—it is the first book by the author in the so-called "Kronen Tetralogy," along with Mensaka, Ciudad rayada, and Sonko95.[6] It was adapted to the screen by director Montxo Armendáriz in 1995[1] and translated both into German—Die Kronen-Bar—and into Dutch.[7][8] The novel has been considered a success[8][9] and a best seller.[10] Literarily speaking, it belongs to Generation X.

Detailed description of the plot[edit]

The novel takes place during the month of July 1992 in the city of Madrid.[11] Carlos is the main protagonist. He's a young university student, barely 21 years old, who is described as a "spoiled brat,"[9] self-centered, and lacking empathy,[12] whose life revolves only around alcohol, drugs, and sex. He often meets his friends at the Kronen, his favorite (fictitious) bar,[13] located in the novel in the vicinity of Francisco Silvela Street in Madrid.[8][14][15] In the book, he is described as a sociopath.[4] Carlos experiences a progressive process of isolation, alienation, and "solipsistic introversion" that eventually leads to the novel's climax,[9] in which the death of one of his friends—Fierro, a diabetic who has a weak personality and whom the gang believes is a homosexual, apart from a masochist—takes place at his own birthday party, resulting from being forced to drink a bottle of whisky through a funnel and putting cocaine on his penis, which leads to a fatal overdose.[16]

Structure and style[edit]

The book's original cover included a silk-screen printing of Andy Warhol's 5 Deaths on Orange (Orange Disaster)—a crashed car with the dead body of a woman underneath it.[19][20] The novel opens and ends with the lyrics from Giant, a song by British band The The.[21][22] Narrated in the first person—through Carlos's point of view—[23] it stresses the dizzying,[24] very fluid rhythm, thanks to the dynamic dialogue that makes up most of the novel,[25] alternated with narrated fragments.[23] The visual component of the novel has also been praised.[26]

In order to emphasize the fleeting and frivolous nature of the novel's narrative, the author makes use of the resource of inserting strings of location names, in which he omits verbs or articles, or even pronouns.[27] Historias del Kronen is also characterized by the precise description of the place where the action unfolds, mentioning real places around Madrid,[28][13] such as the Plaza del Dos de Mayo square,[29] the Parque de las Avenidas park,[30] the Las Ventas bullfighting ring,[31] or the Gran Vía street,[32] among others. The style used by Mañas in the book has been referred to as slightly monotonous. Despite this, he manages to reach a point of narrative tension by the end of the novel.[33] This ending, which culminates in Fierro's death—one of Carlos's friends—has been praised by its original style in the form of a monologue.[9] One hallmark of the narrative is also the constant recurrence to slang expressions used by young people, by putting them in the mouths of the protagonists. In this sense, some of the terms that stand out include the constant use by Carlos of the offensive term cerdas[a] to refer to women;[34][35] neologisms;[36] or the appearance of colloquialisms that refer to the world of drugs, such as: costo,[b] chocolate[c], tripi,[d], farlopa,[e] or nevadito.[f][g][40] The use of offensive or dysphemistic expressions is common in the slang used by the young people in the novel.[41][42] Mañas also resorts to the insertion of numerous musical references in the book,[43] even including song lyrics by bands such as The The, Nirvana[44] (Come as You Are[45] and Drain You[46]), Siniestro Total (Bailaré sobre tu tumba),[46] or Los Ronaldos (Sí, sí).[47]

Context and influences[edit]

Historias del Kronen represents the conversion of the U.S. cultural concept of Generation X to the Spanish society.[48] In fact, it has been considered one of the definitive novels of this generational movement in Spain,[8] which has been called, precisely, "Generation Kronen."[28][49] The novel is considered to be neo-realist in style.[50]

It has been compared to Douglas Coupland's Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture—the novel that popularized the term Generation X—and it has even been mentioned that it could be its "Spanish version."[9] On the other hand, it has been said that Historias del Kronen contains parallelisms with Ernest Hemingway's The Sun Also Rises (1926),[51] Carmen Laforet's Nada (1945),[8] or Juan Marsé's Últimas tardes con Teresa (1966),[8] as well as Rafael Sánchez Ferlosio's El Jarama (1955),[8][4] due to the realism of these novels. Mañas even agreed with this latter comparison, although, according to him, the style is profoundly different.[52] The author has also spoken about the supposedly strong resemblance that Historias del Kronen has with Bret Easton Ellis's Less than Zero (1985),[28][44] saying that both are different as the nature of the former is menos descriptivo y más hosco,[h] as well as more abierto socialmente,[i] apart from claiming that he hadn't read Ellis's first novel before he wrote Historias del Kronen.[15] Mañas mentioned Warhol, Camus's L'Étranger, and Raymond Carver as his main influences.[5]

Criticism[edit]

Positive reviews highlight Mañas's "amazing" ability to capture the language of young people and to use it to set each character apart.[53] The book was very well received by readers thanks to its "authenticity."[54] However, the book has received very mixed reviews, with critics pointing out its supposed nature as a novela cutre,[j] as well as its realismo sucio,[k][52] in a pejorative sense, and also drawing attention to its alleged imitation of the dirty realism that originated in the United States.[54] It has also been said about the book that, by enhancing realism in the narration of the facts as a sort of social commentary, it runs the risk of being only a superficial imitation of the society it is attempting to describe.[55] More critical authors point out that the narration consists of an "endless reiteration of inane conversations" among the characters and the lack of "substance" of the novel, filled with "an incessant chattering, a bit crude, full of unoriginal phrases and conventionalisms."[53] In any case, Historias del Kronen sold more than 100,000 copies, which represented an unprecedented success in Spanish literature at the time.[56]

Analysis and themes[edit]

The novel portrays young people in 1990s Spain, the vacío existencial[m] and isolation of many of them, and their characteristic disillusionment at failing to find their place in the world,[58] with a pessimistic view of existence and the human condition—common aspects in Generation X writers—[59] added to a perspective influenced by nihilism.[60] Sexuality is an essential theme in Mañas's work, describing sexual relations between his characters in a manner that is explícita y desinhibida.[n][61] Several of the male characters that appear in Historias del Kronen display a negative view of homosexuality,[8] in contrast to the revelation about the homosexuality of one of them—Roberto—and the potential bisexuality of Carlos, the main character.[8] Also palpable in the novel is the way that la presión social[o] serves to shape the sexual conduct of the novel's characters.[62] Carlos stresses the importance of the culture of TV, films, and visual media[26] in detriment to poetry and literature.[63]

Cualquier película, por mediocre que sea, es más interesante que la realidad cotidiana. Somos los hijos de la televisión, como dice Mat Dilon en Dragstorcauboi.[p][64]

The non-profit association Fundación para el Progreso de Madrid chose the novel as one of the ten books that best portray the city.[67] The author himself described the book as Kronen era un Madrid visto a través de la ventanilla de un coche que circula por la Emetreinta,[r] referring to Madrid motorway M-30 and highlighting its symbolism and that of peri-urban areas in the novel.[68] The book also highlights the superficial nature of all of Carlos's relationships, with his characteristic inability to develop empathy towards his surroundings[69] and a behavior referred to that of an alpha male.[70] Moreover, the novel stresses the generational gap between Carlos and his family.[71] The character of Carlos's grandfather functions as a showcase and reflection of the evolution of women throughout the 20th century, precisely through the way he clings to the defense of traditional family values, and women's break with traditional patriarchy[72] which, however, female characters in the novel such as Amalia or Nuria—both of whom are friends of Carlos and who at first are introduced as independent women that break the moldes de género—[s] do not manage to overcome completely.[73] The novel mentions the films The Texas Chain Saw Massacre,[5][74] Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer, and A Clockwork Orange, as well as Bret Easton Ellis's novel American Psycho,[75][76] which Carlos claims to be a fan of and ultimately seem to give shape to his misogynistic and violent behavior.[76][77] Mañas has admitted that Historias del Kronen has a certain autobiographical component.[78]

Film adaptation[edit]

A film based on the novel, directed by Montxo Armendáriz, was released in 1995. One of the main differences between the book and the film is the evolution of the character of Carlos—played by Juan Diego Botto—who, while in the novel does not evolve or improve in any way,[63] in the film does experience in the end a sort of reshuffling of his moral values,[79] possibly due to being affected by his grandfather's death,[80] apart from demonstrating a certain concern for his friends.[81] Thus, in general, he turns out to be a more humane and compassionate person than the character in Mañas's book.[79][82]

In the movie, the novel's ending monologue is replaced by a sequence seen through a video camera that is passed around all the people present at the party, in which Pedro's death—Fierro, in the novel—becomes a sort of snuff film.[83][84] The movie was criticized for its slightly moralistic tone.[85] It depicts situations that are not present in Mañas's book, such as one scene in which Carlos steals money from his mother and lets the blame fall on the maid,[85] as well as the most emblematic and well-known scene in the movie—included in the poster—in which two youngsters hang from a bridge over the Paseo de la Castellana thoroughfare in Madrid on a dare to see who lasts the longest.[86] Likewise, the harshness of some comments appears to have been toned down in the film which, in a sense, is an edulcorada[t] version of the book.[87][88]

Sequel[edit]

In 2019, Mañas published La última juerga, a sequel to Historias del Kronen.[89]

References in music[edit]

The novel is mentioned in the song Luis XIV by Spanish rapper Mitsuruggy, from his 2014 album The Coach.[90]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ English: Lit. female pigs

- ^ English: Lit. cost; it refers to poor-quality hashish[37]

- ^ English: Lit. brown, or chocolate bar[37]

- ^ English: Phonetic spelling of trippy: "of, relating to, or suggestive of a trip on psychedelic drugs or the culture associated with such drugs"[38]

- ^ There are several etymological claims: either farlopa comes from the English phrase "parlour powder" used in the 1920s; or from the Italian farlocco, meaning fake; falopa from the Argentine lunfardo slang word for cocaine; and lastly, from the Galician words folerpa and falopa, meaning snowflake[39]

- ^ English: Lit. diminutive form of snow-capped, snow-covered

- ^ English: A nevadito is a joint with cocaine

- ^ English: Less descriptive and more sullen

- ^ English: Socially open

- ^ English: Seedy novel

- ^ English: Dirty realism

- ^ English: Spelling out of M-30 in Spanish

- ^ English: Existential emptiness

- ^ English: Explicit and uninhibited

- ^ English: Peer pressure

- ^ English: Any movie, however mediocre it is, is more interesting than day-to-day reality. We are all TV babies, as Matt Dillon says in Drugstore Cowboy

- ^ The Plaza del Dos de Mayo square, located in the Malasaña neighborhood of Madrid, is a meeting point for young people on the weekend, often to consume alcohol. In the novel, Carlos and his friends meet there before choosing a place or a bar to go to.

- ^ English: Kronen was a Madrid seen through the window of a car crossing the Emetreinta

- ^ English: Gender molds

- ^ English: Watered-down

References[edit]

- ^ a b Brumme 2012, p. 175.

- ^ Moret, Xavier (7 January 1994). "Rosa Regàs gana el Nadal con 'Azul', un relato sobre las dependencias del amor". El País (in Spanish). Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- ^ Henseler & Pope 2007, p. 214.

- ^ a b c Henseler & Pope 2007, p. 105.

- ^ a b c Moret, Xavier (13 January 1994). "Mañas: "Estaba en un agujero negro cuando quedé finalista del Nadal"". El País (in Spanish). Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- ^ Castilla, Amelia (22 October 1999). "Mañas completa con 'Sonko 95' su tetralogía sobre jóvenes de los 90". El País (in Spanish). Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- ^ Mañas 1995.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Foster 1999, p. 103.

- ^ a b c d e Faulkner 2004, p. 67.

- ^ Smith 2005, p. 78.

- ^ Marr 2006, p. 10.

- ^ Gavela 2008, p. 218.

- ^ a b Junkerjürgen 2007, p. 43.

- ^ Fernández Santos, Elsa (28 June 1994). "La generación X encuentra un rostro". El País (in Spanish). Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- ^ a b "Encuentros digitales. Ha estado con nosotros: José Ángel Mañas". El Mundo (in Spanish). 9 March 2005. Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- ^ Foster 1999, p. 104.

- ^ Mañas 1994, pp. 150–155.

- ^ "Concierto de Elton John en las Ventas". El País (in Spanish). 13 July 1992. Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- ^ Rodríguez Aguilar, JB (26 April 2020). ""Generation X" & "Historias del Kronen": literatura de un linaje". JB Rodríguez Aguilar (in Spanish). Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- ^ Henseler 2008, p. 356.

- ^ Henseler & Pope 2007, p. 115.

- ^ Marr 2006, p. 11.

- ^ a b Santos Gargallo 1997, p. 457.

- ^ Santana 2013, pp. 115–116.

- ^ Brumme 2012, pp. 176–177.

- ^ a b Faulkner 2004, p. 69.

- ^ Faulkner 2004, pp. 68–69.

- ^ a b c Henseler 2011, pp. 73–84.

- ^ Mañas 1994, p. 20.

- ^ Mañas 1994, p. 53.

- ^ Mañas 1994, p. 93.

- ^ Mañas 1994, p. 71.

- ^ Capanaga 1995, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Capanaga 1995, p. 53.

- ^ Santos Gargallo 1997, p. 465.

- ^ de Urioste 2004, p. 463.

- ^ a b "Hachís". Química.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ "trippy". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ López, Alfred (3 August 2023). "¿De dónde proviene el término 'farlopa' para referirse a la cocaína?". 20 minutos (in Spanish). Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ Capanaga 1995, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Capanaga 1995, p. 56.

- ^ Santos Gargallo 1997, pp. 467–472.

- ^ Marr 2006, pp. 9–10.

- ^ a b Marr 2006, p. 9.

- ^ Mañas 1994, p. 106.

- ^ a b Mañas 1994, p. 107.

- ^ Mañas 1994, p. 140.

- ^ Brumme 2012, pp. 175–176.

- ^ Parra 2012, p. 10.

- ^ Gullón, Germán. "La novela neorrealista (o de la generación X)". Miguel de Cervantes Virtual Library (in Spanish). Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ Henseler & Pope 2007, pp. 140–141.

- ^ a b Brumme 2012, p. 176.

- ^ a b Santana 2013, pp. 116–117.

- ^ a b Gullón & Martínez-Carazo 2005, p. 143.

- ^ Smith 2005, p. 89.

- ^ Gullón & Martínez-Carazo 2005, p. 142.

- ^ Mañas 1994, p. 25.

- ^ Gavela 2008, p. 219.

- ^ Alchazidu 2009, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Ballesteros 2001, p. 257.

- ^ Casado Díaz 2011, p. 70.

- ^ Casado Díaz 2011, p. 71.

- ^ a b Parra 2012, p. 15.

- ^ "Drugstore Cowboy Quotes". iMDB. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

All these kids, they're all TV babies.

- ^ Mañas 1994, p. 42.

- ^ Smith 2005, p. 88.

- ^ "Escogen los 10 libros que mejor retratan Madrid". ABC (in Spanish). 29 May 2003. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ Díaz de Tuesta, M. José (6 July 2012). "Aires de periferia". El País (in Spanish). Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ Casado Díaz 2011, p. 73.

- ^ Marr 2006, p. 18.

- ^ Parra 2012, p. 14.

- ^ Casado Díaz 2011, p. 75.

- ^ Casado Díaz 2011, pp. 76–77.

- ^ Mañas 1994, p. 92.

- ^ Capanaga 1995, p. 51.

- ^ a b Casado Díaz 2011, p. 83.

- ^ Marr 2006, p. 13.

- ^ Martín Rodrigo, Inés (16 November 2010). "José Ángel Mañas regresa al terreno de la novela negra con "Sospecha"". ABC (in Spanish). Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ a b Gavela 2008, p. 220.

- ^ Parra 2012, p. 16.

- ^ Parra 2012, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Parra 2012, p. 17.

- ^ Faulkner 2004, p. 70.

- ^ Schmelzer 2007, p. 80.

- ^ a b Faulkner 2004, p. 71.

- ^ Junkerjürgen 2007, p. 48.

- ^ Gavela 2008, pp. 220–222.

- ^ Ballesteros 2001, p. 258.

- ^ Jiménez Barca, Antonio (24 November 2019). "'La última juerga': 25 años bebiendo en el Kronen". El País (in Spanish). Retrieved 4 May 2024.

- ^ "The Coach". Mitsuruggy (in Spanish). Retrieved 4 May 2024.

Bibliography[edit]

- Mañas, José Ángel (1994). Historias del Kronen (in Spanish) (1st ed.). Barcelona, Spain: Ediciones Destino. ISBN 842332351X.

- Mañas, José Ángel (1995). Die Kronen-Bar (in German). Hamburg, Germany: Rasch und Röhring. ISBN 9783891365571.

Works cited[edit]

- Alchazidu, Athena (2009). "Tiempo y espacio en "Historias del Kronen", una de las crónicas urbanas de la Generación X". Études romanes de Brno (in Spanish). 30 (2). Brno, Czechia: Masaryk University: 19–28. ISSN 1803-7399.

- Ballesteros, Isolina (2001). Cine (ins)urgente: textos fílmicos y contextos culturales de la España posfranquista (in Spanish). Madrid, Spain: Editorial Fundamentos. ISBN 9788424508838.

- Brumme, Jenny (22 February 2012). "El lenguaje de la Generación X. Historias del Kronen (1994), de José Ángel Mañas, en alemán". Traducir la voz ficticia (Report). Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für romanische Philologie (in Spanish). Vol. 367. Berlin, Germany: de Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110263268. ISBN 9783110263268.

- Capanaga, Pilar (15–16 March 1995). La creación léxica en "Historias del Kronen". Proceedings of the Rome Conference (in Spanish). Rome, Italy: Association of Italian Hispanists. pp. 49–60. ISBN 88-7119-981-2.

- Casado Díaz, Óscar (2011). "La sexualidad en el centro: una lectura feminista de "Historias del Kronen"". Dicenda: Cuadernos de filología hispánica (in Spanish). Estudios de lengua y literatura españolas (29). Madrid, Spain: Complutense University of Madrid: 69–90. ISSN 0212-2952.

- de Urioste, Carmen (July 2004). "Cultura punk: la "Tetralogía Kronen" de José Ángel Mañas o el arte de hacer ruido" (PDF). Ciberletras: Journal of literary criticism and culture (in Spanish) (11: La literatura mexicana de fines del siglo XX). New York, United States: Lehman College: 459–490. ISSN 1523-1720.

- Faulkner, Sally (2004). Literary Adaptations in Spanish Cinema. London, United Kingdom: Tamesis Books. ISBN 9781855660984.

- Foster, David William (1999). Spanish Writers on Gay and Lesbian Themes: A Bio-critical Sourcebook. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313303326.

- Gavela, Yvonne (2008). "XVIII: La imagen como elemento mediador de la realidad ficticia de Historias del Kronen". In Juan-Navarro, Santiago; Torres Pou, Joan (eds.). Memoria histórica, género e interdisciplinariedad: los estudios culturales hispánicos en el siglo XXI (in Spanish). Madrid, Spain: Biblioteca Nueva. pp. 215–226. ISBN 978-84-9742-712-8.

- Gullón, Germán; Martínez-Carazo, Cristina (9 December 2005). "José Ángel Mañas (22 October 1971 - )". In Martínez-Carazo, Cristina; Altisent, Marta E. (eds.). Dictionary of literary biography Vol. 322: Twentieth-century Spanish fiction writers. Gale. pp. 142–147. ISBN 0787681407.

- Henseler, Christine (March 2008). "On Going Nowhere Too Fast: José Ángel Mañas's 'Historias Del Kronen' and the Surface Culture of Andy Warhol". MLN. 123 (2. Hispanic Issue). Johns Hopkins University Press: 356–373. ISSN 0026-7910.

- Henseler, Christine (24 October 2011). "Punked Out and Smelling Like Afterpop". Spanish Fiction in the Digital Age: Generation X Remixed. New York, United States: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 73–84. ISBN 978-1-349-28745-1.

- Henseler, Christine; Pope, Randolph D., eds. (18 June 2007). "Generation X Rocks: Contemporary Peninsular Fiction, Film, and Rock Culture". Hispanic issues. 33. Nashville, Tennessee: Vanderbilt University Press. ISBN 9780826592293.

- Junkerjürgen, Ralf (2007). "1. Panoramas. Cuando Nueva York imitó a Madrid. Perfiles de la capital en el cine español de los años noventa". In Pohl, Burkhard; Türschmann, Jörg (eds.). Miradas glocales: cine español en el cambio de milenio (in Spanish). Madrid, Spain; Frankfurt, Germany: Iberoamericana Vervuert. pp. 39–54. ISBN 9788484893028.

- Marr, Matthew J. (2006). "An Ambivalent Attraction?: Post-Punk Kinship and the Politics of Bonding in Historias del Kronen and Less than Zero". Arizona Journal of Hispanic Cultural Studies. 10. Tucson, Arizona, United States: University of Arizona: 9–22. ISSN 1934-9009. OCLC 76810189.

- Parra, Rubén D. (2012). "El individuo de la Generación X en Historias del Kronen. Un personaje atrapado por y en la sociedad urbana española durante los 90". Divergencias. Revista de estudios lingüísticos y literarios (in Spanish). 10 (2. Winter 2012.). Tucson, Arizona, United States: University of Arizona: 10–19. ISSN 1555-7596. OCLC 59551699.

- Santana, Cintia (27 June 2013). Forth and Back: Translation, Dirty Realism, and the Spanish Novel (1975–1995). Bucknell University Press. ISBN 9781611484618.

- Santos Gargallo, Isabel (1997). "Algunos aspectos léxicos del lenguaje de un sector juvenil: Historias del Kronen de J.A. Mañas". Revista de filología románica (in Spanish). 14 (1). Madrid, Spain: Complutense University of Madrid: 455–474. ISSN 0212-999X.

- Schmelzer, Dagmar (2007). "2. La violencia y lo cómico. La violencia enfocada: tres visiones cinematográficas españolas. La muerte de Mikel (1983) de Imanol Uribe, Historias del Kronen (1994) de Montxo Armendáriz y El bola (2000) de Achero Mañas". In Pohl, Burkhard; Türschmann, Jörg (eds.). Miradas glocales: cine español en el cambio de milenio (in Spanish). Madrid, Spain; Frankfurt, Germany: Iberoamericana Vervuert. pp. 73–87. ISBN 9788484893028.

- Smith, Carter E. (January 2005). "Social Criticism or Banal Imitation? A Critique of the Neo-realist Novel Apropos the Works of José Angel Mañas" (PDF). Ciberletras: Journal of literary criticism and culture (12: La literatura y cultura españolas fines del siglo XX). New York, United States: Lehman College: 78–94. ISSN 1523-1720.

External links[edit]

- Historias del Kronen at IMDb , film adaptation of the novel

- Andy Warhol's 5 Deaths on Orange (Orange Disaster) (1963), artwork depicted on the original cover of the book