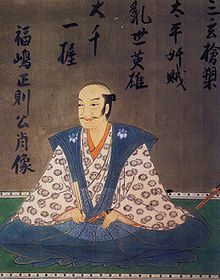

Fukushima Masanori

Fukushima Masanori | |

|---|---|

| 福島 正則 | |

Fukushima Masanori | |

| Lord of Hiroshima | |

| In office 1600–1619 | |

| Preceded by | Mōri Terumoto |

| Succeeded by | Asano Nagaakira |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Ichimatsu 1561 Futatsudera, Kaitō, Owari Province |

| Died | August 26, 1624 (aged 62–63) |

| Nationality | Japanese |

| Spouse | Omasa |

| Parent |

|

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Unit | |

| Battles/wars | Siege of Miki Battle of Yamazaki Battle of Shizugatake Kyūshū campaign Korean campaign Battle of Gifu Castle Battle of Sekigahara |

Fukushima Masanori (福島 正則, 1561 – August 26, 1624) was a Japanese daimyō of the late Sengoku period to early Edo period who served as lord of the Hiroshima Domain. A retainer of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, he fought in the Battle of Shizugatake in 1583, and soon became known as one of Seven Spears of Shizugatake which also included Katō Kiyomasa and others.

Biography[edit]

Fukushima Ichimatsu, was born in 1561, in Futatsudera, Kaitō, Owari Province (present-day Ama, Aichi Prefecture), the eldest son of barrel merchant Fukushima Masanobu. However, it is also said that his father, Masanobu, was his father-in-law. In the latter case, his father is believed to have been cooper Hoshino Narimasa from Kiyosu, Kasugai, Owari Province (present-day Kiyosu, Aichi Prefecture).[1] His mother was the younger sister of Toyotomi Hideyoshi's mother, making Hideyoshi his first cousin.[1]

As a young man, he served as a page (koshō) of Hideyoshi through their mothers' relation.[1]

He first engaged in battle at the assault on Miki Castle in 1578-1580 at Harima Province, and following the Battle of Yamazaki in 1582, he was granted a 500 koku stipend.

At the Battle of Shizugatake in 1583, he defeated Haigo Gozaemon, a prominent samurai.[2] Masanori (Tenshō 11) had the honor of taking the first head, namely that of the enemy general Ogasato Ieyoshi, receiving a 5000 koku increase in his stipend for this distinction (the other six "Spears" each received 3000 Koku), he married with Omasa.

Masanori took part in many of Hideyoshi's campaigns; it was after the Kyūshū Expedition in 1587, however, that he was made a daimyō. Receiving the fief of Imabari in Iyo Province, his income was rated at 110,000 koku. Soon after, he took part in the Korean Campaign. Masanori was to once again receive distinction when he took Ch'ongju in 1592.[3] Following his involvement in the Korean campaign, Masanori was involved in the pursuit of Toyotomi Hidetsugu.

In 1595, Masanori led 10,000 men, surrounded Seiganji temple on Mount Kōya, and waited until Hidetsugu had committed suicide.[4] With Hidetsugu dead, Masanori received a 90,000 koku increase in stipend, and received Hidetsugu's former fief of Kiyosu, in Owari Province as well.[5]

In 1598 after the death of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, the government of Japan have an accident when seven military generals consisted of Katō Kiyomasa, Katō Yoshiaki, Ikeda Terumasa, Kuroda Nagamasa , Asano Yoshinaga, Katō Kiyomasa, and Masanori himself plotted a conspiracy to kill Ishida Mitsunari. It was said that the reason of this conspiracy was dissatisfaction of those generals towards Mitsunari as he underreporting the achievements of those generals during the Imjin war against Korea & Chinese empire.[6] At first, these generals gathered at Kiyomasa's mansion in Osaka Castle, and from there they moved into Mitsunari's mansion. However, Mitsunari learned of this through a report from a servant of Toyotomi Hideyori named Jiemon Kuwajima, and fled to Satake Yoshinobu's mansion together with Shima Sakon and others to hide.[6] When the seven generals found out that Mitsunari was not in the mansion, they searched the mansions of various feudal lords in Osaka Castle, and Kato's army also approached the Satake residence. Therefore, Mitsunari and his party escaped from the Satake residence and barricaded themselves at Fushimi Castle.[7] The next day, the seven generals surrounded Fushimi Castle with their soldiers as they knew Mitsunari was hiding there. Tokugawa Ieyasu, who was in charge of political affairs in Fushimi Castle trying to arbitrate the situation. The seven generals requested Ieyasu to hand over Mitsunari, which refused by Ieyasu. Ieyasu then negotiated the promised to let Mitsunari retire and to review the assessment of the Battle of Ulsan Castle in Korea which became the major source of this incident, and had his second son, Yūki Hideyasu, to escort Mitsunari to Sawayama Castle.[8] Historians viewed this incident were not just simply personal problems between those seven generals against Mitsunari, as it was viewed as an extention of the political rivalries on greater scope between Tokugawa faction and anti-Tokugawa faction which led by Mitsunari, since by this incident, the seven generals including Nagamasa would support Ieyasu later during the conflict of Sekigahara between Eastern army led by Tokugawa Ieyasu and Western army led by Ishida Mitsunari.[6][9]

Campaign of Sekigahara[edit]

In 1600 August 21, The Eastern army alliance which sided with Ieyasu Tokugawa attacked Takegahana castle which defended by Oda Hidenobu, who sides with Mitsunari faction.[10] They split themselves into two groups, where 18,000 soldiers led by Ikeda Terumasa and Asano Yoshinaga went to the river crossing, while 16,000 soldiers led by Masanori, Ii Naomasa, Hosokawa Tadaoki, Kyogoku Kochi, Kuroda Nagamasa, Katō Yoshiaki, Tōdō Takatora, Tanaka Yoshimasa, and Honda Tadakatsu went downstream at Ichinomiya.[11] The first group led by Terumasa crossed the Kiso River and engaged in a battle at Yoneno, causing the Hidenobu army routed. On the other hand, Takegahana castle were reinforced by a Western army faction's general named Sugiura Shigekatsu. The Eastern army led by Naomasa and Fukushima crossed the river and directly attacked Takegahana Castle at 9:00 AM on the August 22nd. Shigekatsu himself setting the castle on fire and committed suicide as a final act of defiance.[10]

On September 29, Masanori, Ii Naomasa and Honda Tadakatsu led their army to rendezvous with Ikeda Terumasa army, where they engaged Oda Hidenobu army in the Battle of Gifu Castle against Oda Hidenobu of the Ishida Mitsunari Western army. In this battle, Hidenobu castle were deprived the expected support from Ishikawa Sadakiyo (石川貞清), who decided to not help the Western army in this war after he made an agreement with Naomasa. Hidenobu was prepared to commit seppuku, but was persuaded by Ikeda Terumasa and others to surrender to the eastern forces, and the Gifu Castle fell.[12][13]

In October 21 At the main battle of Sekigahara, Masanori sided with Tokugawa Ieyasu 'Eastern army' at the Battle of Sekigahara. He was the leader of the Tokugawa advance guard. He started the battle, and charged north from the Eastern Army's left flank along the Fuji River, attacking the Western Army's right center. Masanori's troops fought against Ukita Hideie's army in what is said to have been one of the bloodiest confrontations in the battle. Ukita's troops were winning the battle, pushing back Masanori's army. However, Kobayakawa Hideaki changed sides to support the Eastern army, and later, Masanori's army started winning the fight and the Eastern Army won the battle.

After Sekigahara, Masanori ensured the survival of his domain. Although he later lost his holdings, his descendants became hatamoto in the service of the Tokugawa shōgun.

Forfeit of titles[edit]

Shortly after the death of Ieyasu in 1619, Masanori was accused of breaching Buke Shohatto by repairing a small part of the Hiroshima Castle, which was damaged during the flood caused by a typhoon, without receiving permission. Although Masanori applied for permission two months before, he had not received it officially from the bakufu. It is said that he repaired only the leaky part of the building out of necessity. Although this case was settled down on the condition that Masanori, who was in attendance for his duty in Edo, would apologize and remove the repaired parts of the castle, the bakufu again accused him of insufficient removal of the repaired parts, and as a result, his territories in Aki and Bingo Provinces worth 500,000 koku were confiscated; instead he was given Takaino Domain, one of 4 counties in Kawanakajima, Shinano Province and Uonuma County, Echigo Province worth 45,000 koku.

Nihongo spear[edit]

Nihongo spear (or Nippongo) (日本号): A famous spear that was once used in the Imperial Palace. This is one of The Three Great Spears of Japan. Nihongo later found its way into the possession of Fukushima Masanori, and then Tahei Mori. It is now at the Fukuoka City Museum where it was restored.

In popular culture[edit]

Fukushima Masanori is featured in Koei's video games Kessen, Kessen III, Samurai Warriors, and as a non-playable character in Samurai Warriors 3. He is a playable character in the third installment's expansions, Samurai Warriors 3 Z and Samurai Warriors 3: Xtreme Legends, and in the fourth installment, Samurai Warriors 4 and its subsequent expansions. He is a playable character in Pokémon Conquest (Pokémon + Nobunaga's Ambition in Japan), with his partner Pokémon being Krokorok and Krookodile.[14]

He is mentioned in the movie Harakiri (1962). In the movie his fictional retainer Tsugumo Hanshiro is the protagonist.

Tachi[edit]

Fukushima Masanori's tachi is valued 105 million dollars, and was called "the most expensive sword in the world". It is now in the Tamoikin Art Fund.[15]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Fukushima masanori : Saigo no sengoku busho. Takeichiro Fukuo, Atsushi Fujimoto, 猛市郎 福尾, 篤 藤本. 中央公論新社. 1999. pp. 1, 4, 14. ISBN 4-12-101491-X. OCLC 675273046.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Turnbull, Stephen (1998). The Samurai Sourcebook. London: Cassell & Co. p. 234,240. ISBN 9781854095237.

- ^ Turnbull, Stephen. Samurai Invasion. London: Cassell & Co., p. 120.

- ^ Turnbull, Stephen. Samurai Invasion. London: Cassell & Co., p. 232.

- ^ Berry, Mary Elizabeth. Hideyoshi. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 127–128.

- ^ a b c Mizuno Goki (2013). "前田利家の死と石田三成襲撃事件" [Death of Toshiie Maeda and attack on Mitsunari Ishida]. 政治経済史学 (in Japanese) (557号).

- ^ Kasaya Kazuhiko (2000). "豊臣七将の石田三成襲撃事件―歴史認識形成のメカニズムとその陥穽―" [Seven Toyotomi Generals' Attack on Ishida Mitsunari - Mechanism of formation of historical perception and its downfall]. 日本研究 (in Japanese) (22集).

- ^ Kasaya Kazuhiko (2000). "徳川家康の人情と決断―三成"隠匿"の顚末とその意義―" [Tokugawa Ieyasu's humanity and decisions - The story of Mitsunari's "concealment" and its significance]. 大日光 (70号).

- ^ Mizuno Goki (2016). "石田三成襲撃事件の真相とは". In Watanabe Daimon (ed.). 戦国史の俗説を覆す [What is the truth behind the Ishida Mitsunari attack?] (in Japanese). 柏書房.

- ^ a b 竹鼻町史編集委員会 (1999). 竹鼻の歴史 [Takehana] (in Japanese). Takehana Town History Publication Committee. pp. 30–31.

- ^ 尾西市史 通史編 · Volume 1 [Onishi City History Complete history · Volume 1] (in Japanese). 尾西市役所. 1998. p. 242. Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ 参謀本部 (1911), "石川貞清三成ノ陣ニ赴ク", 日本戦史. 関原役 [Japanese military history], 元真社

- ^ Mitsutoshi Takayanagi (1964). 新訂寛政重修諸家譜 6 (in Japanese). Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ "Masanori + Krokorok - Pokémon Conquest characters". Pokémon. Retrieved 2012-06-17.

- ^ "The Most Expensive Sword in the World - $100 Million Samurai Tachi". World Art News. 5 November 2021. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

External links[edit]

- Biography of Fukushima Masanori (in Japanese)