Separatism in Russia

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

| Federal subjects Субъекты федерации (Russian) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Number | 83 |

Separatism in Russia refers to bids for secession or autonomy for certain federal subjects or areas of the Russian Federation. Historically there have been many attempts to break away from the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union but modern separatism took shape in Russia after the Dissolution of the Soviet Union and the annexation of Crimea.[1] Separatism in modern Russia was at its biggest in the 1990s and early 2000s. The topic became relevant again after the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine. The primary causes of separatism are nationalism in the republics, economic dependency, and geographic isolation. The promotion of separatism is illegal in Russia.[2]

Russian philosopher and regionalist Vadim Shtepa believes that the history of separatism and regionalism in Russia can be divided into 3 parts:[3]

- Russian Imperial (before the 1917 revolution)

- Soviet Imperial (before the dissolution of the Soviet Union)

- Modern Russian Imperial (after the 1993 constitution)

WWI and Russian Empire[edit]

According to Mark von Hagen "delegations of non-Russian deputies to the first Duma [of 1906] actively considered the reconstruction of the empire along democratic and federalist lines with ethno-territorial criteria and measures of cultural autonomy" [4].

In 1916 the organisation known as "Liga of foreign nations of Russia" (German: "Liga der Fremdvölker Rußlands") has been created[5] with German support.

On the background of the First World War the "Congress of the Enslaved Peoples of Russia" has taken place in Kyiv, Ukraine in on 21–28 September 1917, which included 93 representatives of 20 nations.

Arnold Margolin described the attempts to agree about federalization as follows:

"This is where the old story repeated itself. “Russian democracy must come to an agreement with the nationalities [narodnosti],” followed Kerensky's stereotypical response. When I pointed out to him that the Great Russianswere also a nationality and that, on the other hand, the general concept of Russian democracy was composed of the democracies of all nations, he impatiently interrupted me and said that I was “nailing him down". But then he again fell into the same logical error and declared that he considered himself not a Great Russian [velikorossom], but a Russian [russkim]. It turned out that Tseretelli and Matsievich or Vinnichenko should speak on behalf of the nationalities, while Kerensky and Avksentiev should speak on behalf of democracy. And I could not agree with this formulation of the question, since I could not forget for a moment the fundamental truth that Tseretelli is as much a representative of democracy as Kerensky, and that Avksentyev is also not without lineage and tribe, as is Chkheidze or Pip..... [...] A Sultan came to mind [...]. Only this time, instead of the Tsar and the Sultan, representatives of democracy were to speak to the nationalities. And yet, hadn't the Russian socialist revolutionaries [SRs], to whom Kerensky and Avksentiev belonged, demanded at their congress in Moscow (in the summer of 1917) that the nationalities themselves be granted the right to full self-representation or even secession? Now the representatives of democracy were taking this right back. . .[6]"

After the WWI and the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, which contained acknowledgement of the independence for Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Finland, and Ukraine (which signed its own Treaty of Brest-Litovsk) the war between the Soviet government in Moscow, Ukrainian People's Republic and Second Polish Republic has started followed by the Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War.

Soviet Union prior to WWII[edit]

After Soviet Union has been created in 1922, one of the important discussion which occurred between the Soviet Union leadership was the discussion about the role of the national question in the Soviet Union. From Stalin's perspective, independent countries, which were created on the territory of the Russian Empire after 1917 revolution, needed to be convinced to voluntarily give up their independence in exchange for the "real autonomy"[7].

"[...]i.e. replacement of fictitious independence by real internal autonomy of the republics in the sense of language, culture, justice, indoctrination, farming, etc. [...]

3. During the four years of the civil war, when we were forced to demonstrate Moscow's liberalism in the national question because of the intervention, we have succeeded in raising among the Communists, against our will, real and consistent social-independents, who demand real independence in every sense and regard the intervention of the Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party as deceit and hypocrisy on the part of Moscow. [...]

5. If we do not now try to adapt the form of the relationship between the center and the peripheries to the actual relationship, by virtue of which the peripheries must in all essentials unconditionally obey the center, i.e., if we do not now replace formal (fictitious) independence by formal (and at the same time real) autonomy, it will be incomparably more difficult to defend the actual unity of the Soviet republics in a year's time. "

-- Stalin, September 1922

Among the other known movements for liberation, particularly aiming at liberation of Georgia, Azerbaijan, North Caucasus, Ukraine, Turkestan was lead by the organisation called "Prometheus" [8]. According to some reports the Prometheus association was formed in Turkey by various Russian and Caucasian peoples, mostly from those countries which had proclaimed independence from 1917-1923, before Soviet incorporation [9].

After the war the organisation "Prometheus" disappeared and under the polish impact was replaced by another movement - Intermarium (Confederation), which has as its goal the liberation of the states bordering on the Baltic, Black, Adriatic and Aegean seas from Soviet control [9].

Post WWII before dissolution of USSR[edit]

In the midst of WWII, in November 1943, on the territory of occupied Ukraine the organisation known as Anti-Bolshevik Bloc of Nations was created. It remained operational until 1996.

Dissolution of USSR and Crisis of the 90s[edit]

Estonia was the first Soviet republic to declare state sovereignty inside the Union on 16 November 1988. Lithuania was the first republic to declare full independence restored from the Soviet Union by the Act of 11 March 1990 with Georgia joining it over the next two months. Latvia proclaimed the restoration of independency in August 1991. Belovezha Accords between Russia, Ukraine and Belarus were signed in December 1991 and joined by Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Armenia, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Azerbaijan, Georgia and Moldova.

The failure of the Union of Sovereign States project led to Russia taking the place as the successor state to the Soviet Union, leaving uneven distribution of autonomy among the new federal subjects, where the national republics have much more autonomy than the Russian majority regions.[10] It should also be noted that only the republics of Russia signed a treaty giving them autonomy, and Chechnya, despite not signing any treaties with the federal authorities, was still invaded.[11] But by 1993 the treaty principle of federation and the sovereignty of the republics as part of the Russian Federation was not mentioned in the constitution and the old Russian Imperial era symbols, such as the double-headed eagle, were restored.[12]

In the 90s, the idea of Russia becoming a eurasianist Russian nationalist state, separate from the west, became more popular among the elite, which created the idea of "Russian world".[13]

The 1993 crisis also almost caused the collapse of the Russian Federation, with some heads of republics saying that there was a real risk of a civil war.[14]

In 1996 the First Chechen War triggered by the struggle for independence of Chechen Republic of Ichkeria has concluded. The peace has not lasted long and the Second Chechen War began in October 1999, followed up by Vladimir Putin coming to power after the presidential election in May 2000.

In 1999 the Union State treaty with Belarus, attempting the reintegration of Belarus and Russia was signed.

By early 2000s all republics were forced to remove the word sovereign from their constitutions by the Constitutional Court of Russia. This started a trend of even further centralization by the federal government.[15]

Putin's Russia[edit]

Vladimir Putin continued Boris Yeltin's centralization policies by banning regional parties, ending direct gubernatorial elections after the Beslan siege, and by changing titles of heads of republics to head of the republic, instead of president or any other title.

By 2008 the idea of "There is Putin - there is Russia, there is no Putin - no Russia", which was quoted by Vyacheslav Volodin, become popular among some politicians.[16]

Vadim Shtepa believes that by mid-2010s Russia became a failed federation (allegory on failed state) and a postfederal state, where the subjects don't have any actual autonomy.[17]

In 2013 it became illegal to promote separatism.[18] Most of the people arrested or jailed for promoting separatism were discussing it on social networks. Most of the messages did not contain any calls for violence, but only ideas were expressed about the possible independence of one region or another.[19]

2014 following Crimea annexation the war in Donbas, eastern Ukraine began in April 2014.

In 2015, Moscow hosted the conference "Dialogue of nations. The right of peoples to self-determination and the construction of multipolar world". Journalists called it a "congress of separatists." The main organizer of the event was the Anti-Globalization movement of Russia, which is funded by the Russian government. The conference only included separatist movements outside Russia and most of the organizations present had little support or notoriety. This was not the first time Russia used separatism in other countries in its foreign policy.[20]

Members of Russian Government and members of Russian opposition believe that the dissolution of the Russian Federation is one of the biggest threats to modern Russia.[21]

It should also be noted that the understanding of nationality is different from many western countries, due to the fact that during the Soviet era nationality meant ethnic background, thus many separatists devolve into ethnocracy and ethnonationalism, which even happened among some post-Soviet states.[22]

The Russian invasion of Ukraine caused a new rise in separatist activities in the country. Some analysts believe that this invasion may cause a total collapse of the Russian Federation.[23][24][25][26]

Foreign support[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2023) |

Russian government often points at foreign involvement as the primary cause of separatism in Russia, but with the exception of Ukraine, no country directly supported separatists in Russia.

Georgia[edit]

Georgia allowed the transfer of weapons, ammo and Chechen rebels through the Pankisi gorge during the Chechen–Russian conflict.[27]

Finland and Estonia[edit]

Russian sources have accused Finland and Estonia of stirring up separatist sentiment in the Finno-Ugric republics and regions of Russia.[28] Head of the Security Council of Russia Nikolai Patrushev often accused Finland of support separatism in Karelia,[29] going so far as claiming that Finland is creating a battalion of separatists to invade the Republic.[30]

Ukraine[edit]

Ukraine is the only country that openly supports separatist movements in Russia. Since the start of the war in Donbas Ukraine allowed the creation of national battalions. Ukraine is also the only UN member that recognizes the independence of Chechnya, claiming that it's an occupied territory.

On November 9, 2022, deputies of Ukrainian Rada started a motion to recognize Tatarstan and Bashkortostan as occupied territories.[31]

On August 24, 2023, Ukrainian Rada approved the draft resolution on the establishment of the Interim Special Commission of the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine on the development of the basic principles of state interaction with the national movements of small and indigenous peoples of Russia, which would manage the relations between the Ukrainian state and the separatist movements of Russia.[32]

Separatist volunteer battalions[edit]

| Name | Region | Date of formation |

|---|---|---|

| Bashkortostan | 2022 | |

| Chechnya | 2014 | |

| Chechnya | 2022 | |

| Dagestan | 2022 | |

| Karelia | 2023 | |

| Chechnya | 2022 | |

| Siberia | 2023 |

Primary causes[edit]

Ethnic and religious causes[edit]

- Pan-Turkism — Originated in early twentieth century. Mainly supported from Turkey. A consolidating anti-Russian factor for Turkic peoples, also Buryats, Kalmyks and the peoples of the Tungus-Manchu group.[33]

- Siberian regionalism / Siberian Republic — Belief that Russians in Siberia and the Far East warrant autonomy due to their regional distinctiveness. Has its roots in the second half of the 19th century.[34] Geographically and economically isolated regions of the Russian North and Far East often demand more autonomy, isolation causes the local population to preserve or develop its own culture.[35]

- Finno-Ugric nationalism — Considers Finnish-Ugric peoples to be indigenous and entitled to lands throughout the northern half of the European part of Russia, and in Western Siberia. In those subjects of the Russian Federation where there are no local Finno-Ugric ethnic groups, there are enthusiasts who claim to be Finno-Ugric after having an "awakening of national consciousness".[36]

- Quasi-ethnic confederalism and Russian separatism — Exploits dissatisfaction with the policies of the federal center in many areas, tries to create an idea that Russians in the respective regions that make up a separate nation: "Volgars", "Uralians", "Pomors", etc.[36]

These four causes are predominantly secular and do not deny constitutional foundations of the Russian Federation, with the exception of express separatist intentions.[36]

- New religious sects — Neo-pagans can pose a threat only as an additional a factor of aggravation of the situation in the event of a general destabilization.[37]

- Wahhabism — Common in North Caucasus, Tatarstan and Bashkortostan. One of the biggest threats to security in those regions.[38]

Other causes[edit]

- Conflict between regional elites and the central government — became especially common after 2014.[35]

- Organized crime — often uses anti-government rhetoric to gain support among the local population, especially common in the Urals, Siberia and the Far East.[35]

Secessionist movements[edit]

Most of the movements in this list have existed before the collapse of the Soviet Union. These movements have some levels of support among the local population, diaspora, local politicians, and regional elites. Most of the movements are still small in size and have limited support.

Northwestern Federal District[edit]

The main groups pushing for autonomy and separatism within the Northwestern Federal District are Finno-Ugric peoples, but other civic nationalist movements are also prominent in the region. The movements are mainly located in the Kaliningrad, Leningrad and Arkhangelsk Oblasts, as well as in the Karelian and Komi Republics. The movements in the Northwest are influenced by their close proximity to the European Union and NATO.

Baltic Republic[edit]

The Baltic Republic[39][40] (or Land of Amber/Yantarny Krai)[41] is a proposed state within the borders of Kaliningrad Oblast. The idea was mainly supported by the Baltic Republican Party which was dissolved in 2005 and was one of the few openly separatist parties, which were allowed to run in the elections. Members of the Baltic Republican Party were present in Kaliningrad Oblast Duma until the party lost its status as a political party.[42]

Currently, the idea is supported by Kaliningrad Public Movement, which is represented on the Free Nations of Post-Russia Forum, and the Respublika movement.[43] Baltic separatists support decommunization and the use of German city names.[41]

In 2022, the Governor of Kaliningrad Oblast said that there was an attempt to create a "German autonomy" in Kaliningrad by western agents to destabilize the region. It was one of the first mentions of separatism in Russia by governors after the invasion of Ukraine.[44]

Opinion polls and electoral performance[edit]

| Electoral performance of the Baltic Republican Party | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Election | Seats | +/- | Government |

| 2000 Kaliningrad Oblast Duma | 1 / 31

|

Opposition | |

| Reference[42] | |||

Ingria[edit]

Ingermanland or Ingria is a proposed state within the borders of Leningrad Oblast and the city of Saint Petersburg. Ingrian separatism began with Viktor Bezverkhy in the 1970s and 80s, but the concept only gained relative popularity in 1996 with the creation of the Movement for Autonomy of Petersburg and the Independent Petersburg movement.[45] Currently, the idea is supported by the "Free Ingria" movement and "Ingria Without Borders" movement,[46] which are represented in the Free Nations of Post-Russia Forum.[47] The main supporters of Ingermanland are Russians unhappy with the nation's centralization, although in recent times "various groups and movements of Ingria supporters" do not support complete Ingrian independence,[45] while some movements still advocate for full independence.[48] Ethnic Ingrian Finns have unsuccessfully requested the movement to stop using their ethnic flag.[49]

In 2022, a popular Russian rapper Oxxxymiron mentioned Ingria in his anti-war song Oyda in which he says "Ingria will be free", which gave the movements more recognition in the region.[50]

In 2023, activists of "Free Ingria" started to organize an armed group as a part of the Civic Council.[51]

Karelia[edit]

Karelian separatism dates back to the early 1900s, with the creation of the Union of White Sea Karelians and Uhtua Republic. The idea saw a revival in the 90s and early 2000s due to the unofficial status of the Karelian language in Karelia and the Russian economic collapse of 1991–92. The first attempt to break away was in 1992, when Sergei Popov, a member of the Supreme Council of the Republic, proposed to include in the agenda the question of the possibility of secession of the Republic of Karelia from the Russian Federation. He was supported by 43 deputies out of 109.[52]

Promotion of Karelian, Finnish and Veps cultures and languages has been seen as separatism due to western support of those projects. And some delegates of the World Congress of Finno-Ugric Peoples have supported the idea of an independent Karelian state. Some Russian political scientists believewestern support of Finno-Ugric cultures in Russia is a tool used by Finland, Estonia and Hungary to cause the collapse of the country.[28]

The main Karelian separatist organization in the 2010s was the Republican Movement of Karelia, which was legally dissolved in 2019. Despite this, its founder, Vadim Shtepa, also affirms that before and during the dissolution of the Soviet Union there was a popular front in Karelia similar to the Popular Fronts of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, but this claim is unverified.[53] In 2015, a trial began against Vladimir Zavarkin, a deputy of the city council of Suojärvi, who was accused of supporting separatism.[54]

The idea of Karelian separatism is currently supported by the Republican Movement of Karelia and the Karelian National Movement. The Karelian National Movement is represented on the Free Nations of Post-Russia Forum.[47] The main difference between the movements lies in their treatment towards ethnic Russians and other non-Finno-Ugric peoples. The Republican Movement of Karelia supports the idea of a multi-ethnic state based on civic nationalism, while the Karelian National Movement opposes Russians and other non-Finno-Ugric peoples involving themselves in Karelian separatist movements and supports creation of an ethnostate.

In 2023, the Karelian National Movement organized the Karelian National Battalion.

In 2023, there have been arrests of people who planned to join or advocated for others to join the Karelian National Battalion, and arrests over acts of domestic terrorism connected to separatism.[55][56]

Komi[edit]

Komi separatism primarily focuses on the preservation of Komi culture, language, and local ecology.[57][58] Many cultural and language movements, such as Doryam asymös, have been labeled separatist by authorities[59] and some of the members arrested.[60]

Komi government was accused of separatism for their close relations with Finland, Estonia and Hungary.[28]

Promotion of Komi culture and language has been seen as separatism due to western support of those projects. And some delegates of the World Congress of Finno-Ugric Peoples have supported the idea of an independent Komi state. Some Russian political scientists believe western support of Finno-Ugric cultures in Russia is a tool used by Finland, Estonia and Hungary to cause the collapse of the country.[28]

Komi separatists are represented on the Free Nations of Post-Russia Forum.[47]

Pomorie[edit]

Pomorie (sometimes referred to as Biarmia) is a proposed state within the borders of Arkhangelsk Oblast;[58] some movements also include Murmansk Oblast and Nenets Autonomous Okrug as part of a proposed state. The Pomor Institute of Native Peoples supported the idea of a Pomor Republic.[61]

During the Shies protests of 2018–2020, slogans "Pomorie is not a garbage dump" and "No to Moscow garbage" were popular not only in separatist groups but also in general population.[62][63] Nevertheless, an Arkhangelsk journalist Dmitry Sekushin said that the official flag of Arkhangelsk Oblast isn't used by protestors because of potential accusations of separatism.[64] Many Pomor cultural movements have been labeled as separatist for "disuniting Russian culture".[65]

In 2013, a Pomor human rights activist, Ivan Moseev, head of the main Pomor regionalist and cultural organization "Pomor Revival",[66] who worked in NArFU university in Arkhangelsk was accused of inciting hatred against ethnic Russians for his comment on the Internet. He was put on the Russian list of terrorists and extremists. In 2022, the ECHR recognized the case as an infringement of the freedom of speech and awarded him a payment of 8,800 euros.[67][68]

Some Pomor cultural and political organizations demanded a creation of a Pomor Republic within Russia that would include Arkhangelsk Oblast, Komi Republic, Murmansk Oblast, and Nenets AO.[69]

Pomor organization "Pomoṙska Slobóda" were represented by the Karelian National Movement on the Free Nations of Post-Russia Forum.[70]

Southern Federal District[edit]

Separatism in the Southern Federal District is primarily ethnic but some civic nationalist movements are also active. The movements are mainly located in Astrakhan Oblast, Crimea, Krasnodar Krai, Rostov Oblast, and Kalmykia. Some political commentators believe that separatism in that region is funded by Ukraine.[71][better source needed]

Cossackia[edit]

Cossack separatism[39] originates during the Russian Civil War with the proclamation of Almighty Don Host existing from 1918 to 1920. Among a number of Cossack emigrants, the ideas of Cossack nationalism were widespread.[72] Since the collapse of the USSR, several attempts have been made to revive the Don Republic. The Don Cossack Republic was proclaimed in the fall of 1991 and became part of the Union of Cossack Republics of Southern Russia, which planned to become one of the union republics.[73] In March 1993, the Great Cossack circle of the Don approved an act on the transformation of the Rostov region into a state-territorial entity.[74]

Don Cossack separatists seeking the creation of the state of Cossackia are represented on the Free Nations of Post-Russia Forum.[70]

Kalmykia[edit]

Kalmyks moved to the territory of modern Kalmykia in the early 17th century from Central Asia, and at the end of the 17th century Lamaism (a form of Buddhism) spread among the Kalmyks [75].

Kalmyks constitute the majority of the population of Republic of Kalmykia. According to the 2002 census, 292.4 thousand people lived in the Republic of Kalmykia, of whom 155.938 (53.3% of the total population) were Kalmyks, 98.115 (33.6%) were Russians and 38.329 (13.1%) were representatives of other groups (small communities of Dargins, Chechens, Kazakhs, Ukrainians, Avars, Germans, etc.). The non-Kalmyk population is concentrated mainly in Elista and in large settlements bordering Volgograd Oblast [75].

According to the 2010 census, of the 183,000 ethnic Kalmyks, only 80,500 speak their own language. The Kalmyk language is included in the list of endangered languages according to the UNESCO assessment. Despite the difficult situation with the national language, Kalmyks are barely assimilated by Russians [76].

The Kalmyk language has Buzavsky, Torgut and Derbet (or Dyurvyudsky) dialects; the literary language is based on the latter variant. The Derbet dialect is widespread in the Ketchenerovsky District [75].

On July 2-9, 1920, the First All-Kalmyk Congress of Soviets of the Kalmyk People's Workers' Councils was held, which proclaimed the formation of statehood in the form of an autonomous region within the RSFSR. It was attended by delegates from all Kalmyk uluses of Astrakhan and Stavropol provinces, Kalmyks living on the Don and Terek, in Kyrgyzstan, the Urals and the Orenburg region [75].

The Kalmyk Autonomous Oblast was transformed into the Kalmyk ASSR on October 20, 1935, but then liquidated on December 27, 1943, and the Oirat-Kalmyk people were deported.

On January 9, 1957, the Kalmyk Autonomous Oblast was created as part of the Stavropol Krai, which was transformed into the Kalmyk Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic on July 29, 1958.

On October 18, 1990, the Supreme Soviet of the Kalmyk Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic adopted the Declaration of State Sovereignty of the Kalmyk SSR. The Declaration solemnly proclaimed the state sovereignty of the Kalmyk SSR over its entire territory and the determination to create a democratic state based on the rule of law [77].

In 1994, by a decision of President Kirsan Ilyumzhinov and his supporters, the Steppe Statute was approved, which recorded the Republic of Kalmykia as a subject, not a state, as defined in the Constitution of the Russian Federation[78].

Kalmyk separatists seek the creation of an independent Kalmyk state and unification with Astrakhan Oblast.[79] The biggest movement is the Oirat-Kalmyk People's Congress, which emerged in 2015, is represented on the Free Nations of Post-Russia Forum.[47] Promotion of Kalmyk culture has been viewed as separatism by central authorities.[80]

In 2021, Russian police detained several activists during a chuulgan (conventions of activists in Elista). In 2022, Shajin Lama (the spiritual leader of Kalmyk Buddhists) of Kalmykia, Telo Tulku Rinpoche, as well as denounced the Russian invasion of Ukraine [81]. Convention leadership in February 2022 condemned Russian aggression and called on Kalmyks not to participate in the war against Ukraine. In response, Russian authorities imposed administrative measures against members of the Oirat-Kalmyk People's Congress, leading to their forced departure from the Russian Federation[82].

There are general conflict between Kalmyks and Chechens in Liman district reflects relations between Kalmyks and Chechens in Republic of Kalmykia. The Chechen minority, Dagestani diasporas, including Dargins and Avars have shurnk in 2010. All these groups experience tensions, although no large-scale inter-ethnic clashes have been recorded in the republic. Extremely low standard of living is becoming the most serious problem of Kalmykia, contributing to the growth of nationalist and separatist sentiments [82].

Kuban[edit]

Kuban separatism or Kuban Cossack separatism[39][83] originates during the Russian Civil War with the proclamation of Kuban People's Republic. The idea saw revival in the 90s and early 2000s due to revitalization of the Cossack culture.[84] The majority of Kuban separatists identify as Cossack, and, due to subsidization of many Cossack cultural movements, more and more people in Kuban identify as Cossack.[66] In 2017, Kuban Liberation Movement proclaimed independence of Kuban People's Republic, but the stunt received no recognition.[85] Some Russian political commentators believe that Kuban separatism is being founded and supported by Ukraine.[71]

Kuban separatists are represented on the Free Nations of Post-Russia Forum.[48]

North Caucasian Federal District[edit]

Separatism in North Caucasian Federal District is primarily ethnic. Almost all of the republics have an active separatist movement. The primary causes of separatism in this region are ethnic conflicts, poverty, low levels of social development, and radical Islam.[86]

Separatism remains one of the main problems in the region. In the opinion of Chechen publicist Ruslan Martagov, it is impossible to solve this problem within the framework of the Kremlin's current policy in the North Caucasus, since active separatist sentiments “are generated by the Kremlin's inept, provocative policy.”[87]

Circassia[edit]

Circassia is a proposed state that covers the land which was historically inhabited by Circassian people, such as Adygeya (Part of Southern Federal District), north Kabardino-Balkaria, north Karachay–Cherkessia, south-east Krasnodar Krai, and south Stavropol Krai. The independence of Circassia has some support in the republics, but most of the support comes from the Circassian diaspora and International Circassian Association.[88] After the independence of Abkhazia and South Ossetia the separatism in Circassian regions started to grow.[89]

It is estimated that over 5 million people of Circassian origin live in Anatolia, Turkey[90].

Circassian nationalism in Russia is caused by the fact that the Russian government tries to ignore the Circassian issue. Russian government still hasn't recognized the Circassian genocide and refuses to recognize Circassians as the native peoples of the Black Sea coast, the issue became especially discussed during the 2014 Olympic Games, which were held in a former Circassian city of Sochi, Krasnodar Krai. Circassians in Russia and abroad protested the games for ignoring the historical background of the city, but they were ignored by the Russian government. Circassians are also not recognized as one of the native peoples of Krasnodar Krai. There have also been attempts to integrate the Republic of Adyghea into Krasnodar Krai. Since 2014 Circassian separatism and nationalism has been on decline but it's still a threat to the stability of Southern Russia.[91]

Circassia separatist movement is represented by the Council of United Circassia founded 21 January 2023 [92]. In May 2024 the council had been submitting appeals to UN [93] regards to Cirsassian question. Circassia does not recognise the right of the Kuban Cossacks for independence [94] .

Circassian separatists are represented on the Free Nations of Post-Russia Forum.[48]

Chechnya[edit]

Chechen separatism dates all the way back to the 1800s and the Caucasus war. Modern Chechen separatism began with the declaration of independence of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria. After two wars, Chechnya was reincorporated into the Russian Federation. After the war an insurgency movement to restore Chechen independence was started.

The government of Ichkeria is currently in exile.[95] Ichkeria was recognized as "temporarily occupied" by Ukrainian parliament in 2022.[96] Currently there are Chechen volunteers fighting for the Ukrainian army with the goal to restore independence. Other Chechen separatist movements, such as Adat People's Movement, operate independently from Ichkerian government. Chechen separatists are represented on the Free Nations of Post-Russia Forum.[48]

Dagestan[edit]

Modern Dagestan separatism began in the 80s and 90s when radical Islam started to gain popularity among the citizens of the regions.[86] The movement can refer to the idea of an independent united Dagestan or disunited independent states, such as Aghulistan, Avaria, Lezgistan, Darginstan, Lakistan, Rutulstan and Tabarasanstan. Proponents of a united Dagestan want to create a multiethnic state.[97] Some of the local separatist movements have been represented in the UNPO. Dagestani separatism began to gain influence in 2006 after it became a presidential republic, instead of having 14 elected representatives (1 for each of the main ethnic groups). In 2014 the title of President of the Republic of Dagestan was changed to Head of the Republic of Dagestan.[98]

Ingushetia[edit]

Ingush separatism has been growing after the collapse of the Soviet Union due to the fact that the borders between Chechnya, North Ossetia-Alania, and Ingushetia have not been decided upon.[97] Some separatists suggested that Ingushetia should unite with Georgia.[99][100]

In 2023, the Ingush Independence Committee, an organization made up of Ingush migrants in Turkey, was established with the main goal of gaining Ingushetia's independence from Russia.

Committee of Ingush Independence is represented on the Free Nations of Post-Russia Forum.[70]

In 2023, a counter-terrorist operation began in the Republic after attacks on policemen and military personnel.[101]

North Ossetia[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2023) |

Alanian (or Ossetian) separatism refers to the movement to create an independent united Ossetian nation by uniting with South Ossetia.[102][97]

United Caucasia[edit]

Since the creation of the Mountainous Republic of the Northern Caucasus there have been other attempts at creating a unified Caucasian independent state.

Caucasus Emirate[edit]

Caucasus Emirate was a radical movement to create an Islamic state on the territory of North Caucasian Federal District. The group was active from 2007 to 2015, when most of the remaining forces joined in with the Islamic State.

Confederation projects[edit]

The Confederation of Mountain Peoples of the Caucasus (or Confederation of Peoples of the Caucasus) is a proposed state within the borders of Russia's Caucasian republics, South Ossetia and Abkhazia.[103] The symbols used by the separatists are based on symbols of the Mountainous Republic of the Northern Caucasus. The main movement of the separatists is the Confederation of Peoples of the Caucasus, a paramilitary organization that fought in Chechnya, Abkhazia, and South Ossetia. The organization became inactive after its leader, Yusup Soslambekov, was assassinated in 2002.

One of the biggest proponents of a new confederation, which only includes the Russian republics, is the Chechen government in exile, but the idea was rejected by other movements, such as the Committee of Ingush Independence.[104]

Volga Federal District[edit]

Separatism in Volga Federal District is primarily ethnic. All the republics have an active separatist movement. Just like in the Caucasus, the history of Volga separatism dates all the way back to the Tsarist era and many of the national uprisings, such as the Bashkir uprising.

Bashkortostan[edit]

Modern Bashkir separatism began in the 90s and was influenced by Tatarstan.[105] Just like most other movements, Bashkir separatism continued to grow in the early 2000s and even got some support from the local government.[106] In 2020, separatists joined the protests against the occupation of the Kushtau mountain.[107][108] Some Bashkir separatists, such as the Bashkort movement and Bashkir National-Political Center of Lithuania, support a creation of a multiethnic state for both Bashkirs and Russians.[107] But some separatists support a creation of an ethnostate.[109] Bashkir separatists are represented on the Free Nations of Post-Russia Forum.[48]

After the Russian Invasion of Ukraine, there have been reports of armed resistance in Bashkortostan[110] and a company of the Ukrainian armed forces was created with the goal of establishing an independent Bashkir state.[111]

Chuvashia[edit]

Chuvash separatism focuses on the preservation of Chuvash language of culture and the creation of an independent Chuvash Republic or Volga Bulgaria.[112] The main organizations are the Union of Chuvash local historians, Suvar movement, and Chuvash National Congress.[113][112]

Chuvash paganists were criticized by the Russian Orthodox Church for being separatists.[114]

Chuvash separatists are represented on the Free Nations of Post-Russia Forum.[115]

Erzyan Mastor[edit]

Erzyan Mastor (Land of Erzya) is a proposed state by the Erzya National Congress. The movement claimed the territories of Republic of Mordovia, Penza, Ulyanovsk, Nizhny Novgorod, Ryazan, and Samara Oblasts.[116] The movement wants to create a federative state with a Moksha autonomy.[117]

Erzyan separatists reject the idea of existence of a Mordvin ethnicity or nation, believing that it's a made-up term by the colonizers to destroy the cultures of Erzyans and Mokshans.[69]

Promotion of Erzyan and Mokshan cultures and languages has been seen as separatism due to western support of those projects. And some delegates of the World Congress of Finno-Ugric Peoples have supported the idea of an independent Mordvin state. Some Russian political scientists believe that western support of Finno-Ugric cultures in Russia is a tool used by Finland, Estonia and Hungary to cause the collapse of the country.[28]

The movement is represented on the Free Nations of Post-Russia Forum.[47]

Idel-Ural[edit]

The idea of a unified Idel-Ural began during the Russian Civil War with the creation of the Idel-Ural State. The name was later used by the Idel-Ural Legion of Nazi Germany during the invasion of the Soviet Union.

The main movement of modern Idel-Ural separatists is the Free Idel-Ural movement, which was registered in 2018 in Kyiv.[118] The movement wants to create a multi-ethnic federal state.[119]

The Free Idel-Ural movement is represented on the Free Nations of Post-Russia Forum.[47]

Mari-El[edit]

Modern Mari separatism began with the collapse of the USSR. The biggest political organization of Mari nationalists is Mari Ushem, which is over 100 years old. While not separatist in nature, some of its members have expressed separatist ideas. Other movements include Kugeze mlande, a far-right separatist organization, Mari Mer Kagash, and the Association of Finno-Ugric Peoples.[120] Mari paganists were also criticized by the Russian Orthodox Church for being separatists.[121]

Promotion of Mari has been seen as separatism due to western support of those projects. And some delegates of the World Congress of Finno-Ugric Peoples have supported the idea of an independent Mari state. Some Russian political scientists believe that western support of Finno-Ugric cultures in Russia is a tool used by Finland, Estonia and Hungary to cause the collapse of the country.[28]

Mari separatists are represented on the Free Nations of Post-Russia Forum.[115]

Tatarstan[edit]

Modern Tatar separatism began in 1990, when Tatar ASSR declared its sovereignty from the USSR and the RSFSR. On October 18, 1991, the Republic of Tatarstan declared its full independence.[122] In 1992 an independence referendum was held, in which more than 50% voted for full independence from Russia.[123] In 1994, Tatarstan unified with Russia as an associated state, this agreement ended in 2017.

In 2008, Tatarstan government in exile and the Milli Mejlis of the Tatar People declared independence of Tatarstan after the Russo-Georgian war.[124] However, this declaration was ignored by the United Nations.

By 2021, the government of Tatarstan refused to change the title of its president to the head of the republic as per a national order, which was interpreted by some political commentators as separatism.[125] The republic finally yielded to Moscow's pressure in 2023.

Many political scientists and commentators believe that Tatarstan is the leading separatist force in modern Russia and an example for other movements.[126] The main Tatar separatist movements are the All-Tatar Public Center, Tatarstan government in exile, the Milli Mejlis of the Tatar People, and the Ittifaq Party, which used to legally operate in the Russian Federation until their ban in late 2010s.[66] They are represented on the Free Nations of Post-Russia Forum.[48]

Opinion polls and electoral performance[edit]

| 1992 Tatarstan referendum[123] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Do you agree that the Republic of Tatarstan is a sovereign state, a subject of international law, building its relations with the Russian Federation and other republics, states on the basis of equal treaties? | ||

| Yes | No | Invalid |

| 61,39% (1,309,056 votes) | 37,25% (794,444 votes) | 1,35% (28,851) |

Udmurtia[edit]

Udmurt separatism focuses on protection of local culture, language and the creation of an Udmurt state.[127] Udmurt separatism is supported by various Finno-Ugric organizations.[128] The main organizations are Congress of Peoples of Udmurtia and Udmurt Kenesh movement.[127] Many ethnic Udmurts were not allowed to have seats in local parliaments due to fears that they might cause more separatism in the republic.[127]

In 2019, Udmurt linguist and activist Albert Razin committed self-immolation due to Russia's new laws on its native languages.[129] He became a symbol of Udmurt separatists and activists.[130]

Promotion of Udmurt culture and language has been seen as separatism due to western support of those projects. And some delegates of the World Congress of Finno-Ugric Peoples have supported the idea of an independent Udmurt state. Some Russian political scientists believe that western support of Finno-Ugric cultures in Russia is a tool used by Finland, Estonia and Hungary to cause the collapse of the country.[28]

Udmurt separatists are represented on the Free Nations of Post-Russia Forum.[115]

Ural Federal District[edit]

Separatism in the Ural Federal District is primarily represented by the Ural Republic separatists.

Ural Republic[edit]

The Ural Republic is a proposed state within the border of Sverdlovsk, Chelyabinsk, Kurgan and Orenburg Oblasts, and Perm Krai.[39]

Originally the idea was suggested by the Governor of Sverdlovsk Oblast, Eduard Rossel, in 1992, but it was not separatist in nature. In July 1993 Sverdlovsk Oblast Council proclaimed a new federal subject of Russia — Ural Republic. In September, a treaty was signed heads of Kurgan, Orenburg, Perm, Sverdlovsk, and Chelyabinsk regions on their intention to participate in the development of joint local economic union of the Ural Republic. On November 9, 1993, President Yeltsin liquidated the Ural Republic by decree and dissolved the Sverdlovsk Oblast council. Russian government figures believed that creating a majority Russian republic will resolve in the dissolution of Russia.[131]

The main movements are the Ural Republic Movement, Free Ural, and The Ural Democratic foundation.[132][133][134] But political scientists believe that modern Ural separatists and regionalists don't have a single big structure that would unite the smaller movements. The local elite have much less sway over the federal government, compared to the republics, which prevents growth of separatism in the region.[66]

Ural separatists are represented on the Free Nations of Post-Russia Forum.[115]

Siberian Federal District[edit]

Separatism in the Siberian Federal District is primarily represented by the Siberian separatists and ethnic separatists in the republics.

Siberia[edit]

Siberian separatism started to develop after the publication of proclamations "To the Patriots of Siberia" by Nikolay Yadrintsev, one of the founders of Siberian regionalism. He is also one of the first people to advocate non-ethnic separatism in Russia, stating that the unity of language and faith does not serve as an obstacle to separation of the same people into different states.[135]

Modern Siberian separatism began late 80s, when students of the Tomsk University students, who tried to create a pro-independence political party in May 1990. Siberian separatism was especially common among anarchists, especially anarcho-syndicalists. Tomsk was the centre of Siberian separatism, while movements in Novosibirsk and Omsk were more autonomy focused. Idea of an independent Siberia was supported by the intelligentsia and some of the workers effected by the privatization.[136]

In 1991 the Siberian Independence party was created, but it was dissolved in 1993 after not gaining enough support.

In September 1993 during the Russian constitutional crisis, when Siberian governors and deputies demanded simultaneous presidential and parliamentary elections. They also announced the creation of a new federal subject of Russia — the Siberian Republic —, and claimed that if their demands were not met, they would stop the export of all resources and the payment of taxes to the federal center.[137]

In 1997, Siberian deputies and governors created a new political party that defended interests of Siberian and Far Eastern regions and called for more autonomy, their end goal was winning presidential elections.[138]

In early 2000s, local activists in Tomsk tried to create a new language based on Old Siberian dialects, but the group was banned by 2010s.[139]

There are many Siberian regionalist movements, but the largest one was the March for Federalization of Siberia in 2014. The movement also coined the phrase "Stop feeding Moscow!", which is now used by other separatists.[140]

The main causes of separatism are economic dependence and Chinese influence over Siberian economy and ecology.[141]

Siberian separatists are represented on the Free Nations of Post-Russia Forum.[48] Siberian separatists organized a pro-Ukrainian volunteer unit in 2023 as a part of the Civic Council.[142]

Siberian separatism only becomes a threat during a time of crisis, as most Siberians don't have their own national identity, during a poll held in Omsk in 2010, more than 70% of respondents believed that Siberians and Russians are the same people.[136]

Opinion polls[edit]

| Support for autonomy within Russia in 1993 | Support for independence in late 1990s | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | Early 1993 | Late 1993 | Region | Yes | No | Undecided |

| Novosibirsk | 20% | 12% | Novosibirsk oblast | 1/3 | 1/3 | 1/3 |

| Kemerovo oblast | 46% | 1/3 | 1/5 | |||

Tuva[edit]

Tuvan separatism was at its strongest in the early 2000s, when various movements such as Free Tuva protested the new Tuvan constitution.[143][144] The first modern Tuvan separatist organizations began in the 80s, with the creation of the Kaadyr-ool Bichildea movement. Other separatist organizations of pre-2000s include the People's Party of Sovereign Tuva and People's Front of Tuva.[145]

Tuvan separatism is aided by the fact that Tuva is one of the poorest regions of Russia, and ethnic Russians are a very small minority in the Republic.[145]

Tuvan separatists are represented on the Free Nations of Post-Russia Forum.[115]

Far Eastern Federal District[edit]

Separatism in the Far Eastern Federal District is primarily pushed for by Buryats, and Russians concerned about economic dependence on Moscow or economic exploitation.

Buryatia[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2023) |

Buryat separatism may refer either to the idea of an independent Buryat state[146] or the idea of Buryatia uniting with Mongolia.[147] The biggest Buryat separatist movement is the Free Buryatia Foundation, which, while not advocating for full independence, is represented on the Free Nations of Post-Russia Forum.

On March 10, 2023 the organization was entered by the Ministry of Justice of the Russian Federation in the register of “foreign agents”. On September 1, 2023, it became known that the foundation was declared an “undesirable organization” in Russia.[148]

Vladimir Khamutayev is a Buryat dissident, professor, doctor of historical sciences, who emigrated to the United States in 2015. The reason for emigration was persecution by the authorities after Vladimir published his book “Buryatia's accession to Russia: history, law, politics”,[149] which refutes the myth of Buryat-Mongolia's voluntary annexation to Russia. The Russian authorities declared the professor a separatist and opened a criminal case against him. Together with Vladimir Khamutayev, Marina Khankhalaeva co-founded the national movement “Tusgaar Buryad-Mongolia” (“Independence of Buryat-Mongolia”, the pre-revolutionary name of Buryatia). In 2023, as a leader of the movement, Khanhalaeva spoke at the European Parliament within the Forum of Free Peoples of Russia: she told about the forced Christianization of Buryats, the suppression of national resistance, collectivization, repressions of the 30s, destruction of Buddhist temples, religious objects and religious books. Marina also mentioned the disbanding of the Buryat autonomous districts that are now part of Irkutsk Oblast and Trans-Baikal Krai; spoke about the current plight of the Buryat language and the racism that Buryats suffer outside their republic.[150][151]

Far Eastern Republic[edit]

The Far Eastern Republic is a proposed state within the border of the entire Far Eastern Federal District, excluding Sakha and Buryatia.[39] The separatists see the proposed republic as the continuation of the Far Eastern Republic.[152] The idea of an autonomous republic was supported by the former Governor of Khabarovsk Krai, Viktor Ishayev. The biggest current movement is the Far Eastern Alternative which participated in various anti government protests.[153] Other movements, such as the Far Eastern Republican Party, also existed.[154] During the 2020–2021 Khabarovsk Krai protests, some people advocated for the independence of Khabarovsk Krai.[155] Far Eastern separatism is primarily caused by economic dependence on Moscow.[156]

The biggest current regionalist/separatist movement is "Movement for a Far Eastern Republic".[66]

Far Eastern separatists are represented on the Free Nations of Post-Russia Forum.[115]

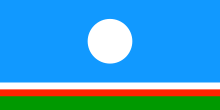

Sakha[edit]

Sakha or Yakut separatism seeks the creation of an independent Yakutian state.[157] The primary cause of Yakut separatism is economic exploitation by the federal government.[157][158] Some journalists and politicians suggested that Turkey supports Sakha separatism financially and politically.[158]

Yakutia is a region that is extremely important for the Russian Federation in terms of geopolitics. Russian propagandist Alexander Dugin in his magnum opus “Foundations of Geopolitics” writes: “Yakutia has such a strategic location, which gives all the prerequisites for becoming an independent region, independent of Moscow. This is ensured by the long coastline, the meridional structure of the republic's territories, and its technical detachment from other Siberian regions. Under certain circumstances, Yakutia may become the main base of the Atlanticist strategy, from which the thalassocracy will restructure the Pacific coast of Eurasia and try to turn it into a classic rimland controlled by the “sea power. The increased attention of the Atlantists to the Pacific area and Makinder's highly indicative allocation of Lenaland to a special category and then inclusion of this territory in the rimland zone in the maps of the Atlantists Speakman and Kirk indicate that at the first opportunity, the anticontinental forces will try to take the region weakly connected with the center out from under the Eurasian control”. At the same time, Dugin draws attention to the existence of a tradition of political separatism in Yakutia, although artificial, but still fixed. [159]

As early as the Soviet period, the region witnessed quite active separatist tendencies. Thus, according to researcher Valery Yaremenko, “there is data on the uprisings of Yakuts and Nenets, against whom military aviation was used in December 1942. Daring and very successful raids of the rebels forced the authorities to create a special body of operational leadership to eliminate them”.[160]

There is also a religious basis for Yakutia's national-separatist movement. Back in the 1990s, some representatives of local intelligentsia (L. Afanasyev, I. Ukhkhana, etc.) developed the doctrine of Yakut neo-paganism. Thus, in 1993 the pagan community “Kut-Syur”, called “Aiyy's doctrine” and representing a modernized Yakut version of the common Turkic religion - Tengrianism - emerged. Moreover, local pagans consider the Yakuts to be the “chosen people” who have preserved the true, original faith. “... Dreams about the high mission of Yakuts, who should return the true faith of their ancestors - Tengrianism - to the Turks of the whole world, are not limited only to the Turkic world. Sometimes in their speeches sound hopes that Russians, Europe, and America will someday be able to return to the path of truth...”[161]

In due time, the AiYi teachings were introduced by the Ministry of Education of Yakutia into the teaching plans of secondary, specialized secondary and higher educational institutions. The College of Culture, which trains specialists for Houses of Culture, actually turned into a center for training specialists in conducting pagan rites, prayers and festivals.[162]

The biggest movement is the Free Yakutia Movement, which is represented on the Free Nations of Post-Russia Forum.[46]

Ethnic Russian separatism[edit]

In mid 2010s the National Democratic Alliance advocated for creation of Russian national republics. The party leader, Alexey Shiropaev, expressed doubts about the unity of the Russian people and considers Russian nation as a conglomerate of sub-ethnic groups that differ both psychologically and physiologically. He advocated Russian separatism, believing that it will be easier to defend the interests of Russians in a few small Russian states than in a large multinational empire. Shiropaev supported the idea of dividing Russia into seven Russian republics and turning it into a "federative commonwealth of nations."[163]

Alexey Shiropaev proposed to transform the Central Federal District into the Republic of Zalessian Rus and form a "Zalessian self-consciousness" in it. A Russian neo-nazi Ilya Lazarenko leads the separatist movement "Zalessian Rus".[164] He currently resides in Cyprus.[165]

One of the founders of the movement, Alexey Shiropaev, later turned to far-right Russian nationalism.[166]

Minor movements[edit]

Many other small separatist movements exist within Russia, but most of them have little to no support and function as online groups.

Irredentism in Russia[edit]

Many peoples living in Russia are related or identical to the titular ethnic groups of neighboring countries. In some regions of Russia and neighboring countries, irredentist ideas about the reunification of divided peoples are being expressed by some of the local population. But most separatist movements are not interested in joining other countries, while some movements want to join organizations like the European Union, they do not seek a new overlord.[167]

In Kazakhstan, nationalist circles often voice demands for the return of Orenburg (formerly the capital of the Kazakh (then Kyrgyz) ASSR in 1920) and the southern part of the Omsk Oblast and the Astrakhan Oblast.[168]

Legal aspects[edit]

In various regions, governors have begun to set up “headquarters to prevent threats of emergence and spread of separatism, nationalism, mass riots and extremist crimes”. So far, three cases are reliably known - in the Republic of Buryatia, Voronezh and Oryol regions.[169]

See also[edit]

Bibliography[edit]

- Ремизова, М.В. (2013). Карта этнорелигиозных угроз: Северный Кавказ и Поволжье (in Russian). Moscow: Институт национальной стратегии.

- Шнирельман, В.А. (2015). Арийский миф в современном мире (in Russian). Moscow: НЛО. ISBN 9785444804223.

- Штепа, Вадим (2012). INTERREGNUM. 100 вопросов и ответов о регионализме (in Russian). Petrozavodsk: Изд. ИП Цыкарев А.В. ISBN 978-5-9903769-1-5.

- Штепа, Вадим (2019). Возможна ли Россия после империи? (in Russian). Yekaterinburg: Издательские решения. ISBN 978-5-4496-0796-6.

References[edit]

- ^ "Russia toughens up punishment for separatist ideas – despite Ukraine". The Guardian. 24 May 2014. Archived from the original on 21 February 2023. Retrieved 21 February 2023.

- ^ "How 'separatists' are prosecuted in Russia Independent lawyers on one of Russia's most controversial statutes". Meduza. 21 September 2016. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 21 February 2023.

- ^ Штепа 2019, p. 107.

- ^ Holian, Anna (30 August 2011). Between National Socialism and Soviet Communism: Displaced Persons in Postwar Germany. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-11780-2.

- ^ Zetterberg, Seppo (1978). Die Liga der Fremdvölker Russlands 1916-1918 [The League of Foreign Nations of Russia 1916-1918] (PDF) (in German). Helsinki.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Margolin, Arnold (1922). Украина и политика Антанты : (записки еврея и гражданина) [Ukraine and Entente politics : (notes of a Jew and a citizen)] (in Russian).

- ^ "Сталин Ленину по вопросу автономизации сентябрь - 1922 г." ["From Stalin's report to Lenin on the question of autonomization" - September 1922]. his95.narod.ru (in Russian). 2001. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ "Роман Смаль-Стоцький. «Український Прометей» національно-визвольного руху народів СРСР" [Roman Smal-Stotsky. The “Ukrainian Prometheus” of the National Liberation Movement of the Peoples of the USSR]. szru.gov.ua (in ua). Retrieved 24 May 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ a b "Petlurians and Prometheus" (PDF). CIA Archives.

- ^ Штепа 2019, p. 41.

- ^ Штепа 2019, pp. 45–47.

- ^ Штепа 2019, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Штепа 2019, p. 44.

- ^ "Октябрь 1993. Хроника переворота. 28 сентября. Республики". old.russ.ru. Retrieved 4 July 2023.

- ^ Штепа 2012, p. 75.

- ^ Штепа 2019, pp. 58–61.

- ^ Штепа 2019, p. 87.

- ^ Новости, Р. И. А. (29 December 2013). "Пять лет лишения свободы грозит за призывы к сепаратизму в России". РИА Новости (in Russian). Retrieved 4 September 2023.

- ^ Штепа 2019, p. 77.

- ^ Штепа 2019, pp. 73–80.

- ^ Штепа 2019, pp. 88–90.

- ^ Штепа 2019, pp. 96–98.

- ^ "Russia Will Collapse in 3-5 Years. The West Must Discuss the Scenarios Now". European Pravda. Retrieved 4 July 2023.

- ^ "Putin's War in Ukraine Could Mean the Collapse of Russia". American Enterprise Institute - AEI. Retrieved 4 July 2023.

- ^ Motyl, Alexander (13 May 2022). "Prepare for the disappearance of Russia". The Hill. Retrieved 4 July 2023.

- ^ "Vadim Štepa: tuntud politoloog ennustab, et Venemaa laguneb Kremli tahtest sõltumatult ja Eesti saab tagasi Tartu rahu järgsed piirid". Eesti Päevaleht (in Estonian). Retrieved 19 February 2024.

- ^ Kleveman, Lutz, 'The New Great Game', Grove Press New York, 2003 page 35; sourced from New York Times August 15, 2002.

- ^ a b c d e f g Иванов, Василий Витальевич (2013). "Национал-сепаратизм в финно-угорских республиках РФ и зарубежный фактор" (PDF). Проблемы национальной стратегии. 21 (6): 95–110.

- ^ "Николай Патрушев обнаружил "финских реваншистов" в Карелии". dp.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ "Патрушев рассказал, как Запад стимулирует сепаратизм в Карелии". РИА Новости (in Russian). 31 July 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ "Украина напомнила Татарстану о независимости. Что об этом думают активисты и российские депутаты". RFE/RL (in Russian). 11 November 2022. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ "Украинские парламентарии создадут комиссию по взаимодействию с национальными движениями народов России". RFE/RL (in Russian). 24 August 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ Ремизова 2013, p. 2.

- ^ Ремизова 2013, pp. 2–3.

- ^ a b c Шатилов, Александр (2021). "НОВЫЙ РЕГИОНАЛЬНЫЙ СЕПАРАТИЗМ В РОССИЙСКОЙ ФЕДЕРАЦИИ (2014-2021 ГГ.)". Власть. 4: 23–26.

- ^ a b c Ремизова 2013, p. 3.

- ^ Ремизова 2013, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Ремизова 2013, pp. 4–8.

- ^ a b c d e Шатилов, Александр Борисович (2021). "НОВЫЙ РЕГИОНАЛЬНЫЙ СЕПАРАТИЗМ В РОССИЙСКОЙ ФЕДЕРАЦИИ (2014–2021 гг.)". Власть. 4: 22–26. Archived from the original on 21 January 2023. Retrieved 21 January 2023.

- ^ Goble, Paul (2 August 2017). "Kaliningrad Separatism Again on the Rise". Jamestown. Archived from the original on 6 October 2022. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ a b "Янтарный край – Балтийская Республика или заложник кремлевской империи?". Регион.Эксперт (in Russian). Archived from the original on 2 January 2023. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ a b "КАЛИНИНГРАДСКАЯ ОБЛАСТЬ". www.panorama.ru. 2001. Retrieved 7 July 2023.

- ^ "БРП: история с продолжением". Регион.Эксперт (in Russian). Archived from the original on 1 January 2023. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ "Патрушев заявил о попытках создания в Калининграде "немецкой автономии"". РБК (in Russian). 21 June 2022. Archived from the original on 2 January 2023. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ a b "Что такое Ингерманландия и чего хотят ее сторонники? Краткая история одной идеи из 1990-х годов". Meduza (in Russian). Archived from the original on 2 January 2023. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ a b ""Я обязательно выучу названия этих 34 государств" В Европейском парламенте прошел "Форум свободных народов России". Его участники хотят разделить страну на несколько десятков государств. Репортаж "Медузы"". Meduza (in Russian). Archived from the original on 3 February 2023. Retrieved 4 February 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f "Политики и эксперты обсудят в польском Гданьске независимость Карелии, Ингрии, Кёнигсберга и других регионов России". RFE/RL (in Russian). 20 September 2022. Archived from the original on 27 March 2023. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g Coalson, Robert (6 January 2023). "Coming Apart At The Seams? For Russia's Ethnic Minorities, Ukraine War Is A Chance To Press For Independence From Moscow". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Archived from the original on 25 January 2023. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ Взятышева, Виктория; Кудрявцева, Анастасия (28 December 2017). "Почему нельзя путать ингерманландских финнов и "Свободную Ингрию"?". «Бумага» (in Russian). Archived from the original on 2 January 2023. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ "Russian 'Internet safety' advocacy group denounces rapper Oxxxymiron for lyrics allegedly calling for St. Petersburg's secession". Meduza. Archived from the original on 2 January 2023. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ "Ингрия возродится в Украине?". Регион.Эксперт (in Russian). Retrieved 4 July 2023.

- ^ ""Нужны не земли, а люди". Может ли Карелия отделиться от России?". Север.Реалии (in Russian). 29 January 2023. Archived from the original on 22 March 2023. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- ^ "Vadim Štepa: Eesti ja Karjala, iseseisvus ja ike". Eesti Päevaleht (in Estonian). Archived from the original on 2 January 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "Когда развалится Россия: Воссоединятся ли братские Финляндия и Карелия". www.depo.ua (in Russian). Archived from the original on 26 February 2020. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ ""Насилие для нас омерзительно". Студента в Карелии обвиняют в подготовке теракта". Север.Реалии (in Russian). 12 March 2023. Archived from the original on 12 April 2023. Retrieved 12 April 2023.

- ^ "В Карелии 18-летнего студента арестовали по делу о госизмене". Радио Свобода (in Russian). 9 March 2023. Archived from the original on 12 April 2023. Retrieved 12 April 2023.

- ^ "Это земля наших предков — они стоят и смотрят на нас Антимусорные протесты на станции Шиес привели к подъему националистов в республике Коми. Они недовольны "колониальной политикой"". Meduza (in Russian). Archived from the original on 2 January 2023. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ a b Чемашкин, Андрей; Шихвердиев, Ариф (February 2022). "Индигенный сепаратизм в Арктической зоне России как фактор риска национальной безопасности" (PDF). Россия и АТР (in Russian) (2): 31–32. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 September 2022. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ ""Опасная" приграничность". Север.Реалии (in Russian). 11 September 2019. Archived from the original on 2 January 2023. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ "Защитить себя родным языком: Активист из Республики Коми отказался от суда на русском". RFE/RL (in Russian). 16 February 2021. Archived from the original on 2 January 2023. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ "Поморский сепаратизм засудят в зародыше". tvrain.tv (in Russian). 22 November 2012. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ Solovyova, Yelena (6 July 2019). "Protests in Shiyes: How a Garbage Dump Galvanized Russia's Civil Society". The Moscow Times. Archived from the original on 7 May 2023. Retrieved 7 May 2023.

- ^ "Не Поморье – не помойка". Регион.Эксперт (in Russian). Archived from the original on 31 March 2023. Retrieved 7 May 2023.

- ^ ""Опасный" поморский флаг". Регион.Эксперт (in Russian). Archived from the original on 7 May 2023. Retrieved 7 May 2023.

- ^ ""Мы на своей земле не хозяева"". www.kommersant.ru (in Russian). 11 June 2012. Archived from the original on 6 November 2022. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Витковская, Татьяна; Назукина, Мария (2021). "ТРАЕКТОРИИ РАЗВИТИЯ РЕГИОНАЛИЗМА В РОССИИ: ОПЫТ СВЕРДЛОВСКОЙ ОБЛАСТИ И РЕСПУБЛИКИ ТАТАРСТАН". Мир России. Социология. Этнология (1): 68–81.

- ^ "Pomor Ivan Moseev turns to European Court of Human Rights". Barentsobserver. Archived from the original on 14 March 2023. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ "European court rules Russia violated Arkhangelsk activist's rights". The Independent Barents Observer. Archived from the original on 1 February 2023. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ a b Шабаев, Юрий; Александр, Садохин (2012). "Новые этнополитические конструкты в региональной практике современной России". Вестник Московского университета. 19 (4): 65–67.

- ^ a b c "Imperial Russia: Prospects for Deimperialization and Decolonization 31/01/2023 European Parliament". YouTube. 31 January 2023. Archived from the original on 31 January 2023. Retrieved 31 January 2023.

- ^ a b "Истоки сепаратизма на Кубани: украинский национализм и пример Татарстана". EADaily (in Russian). 24 December 2015. Archived from the original on 3 January 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "Потомки Илиноя и Сколопита: идеология казачьего национализма". EADaily (in Russian). 19 May 2018. Archived from the original on 8 February 2023. Retrieved 12 April 2023.

- ^ "КАЗАЧЕСТВО И СОВРЕМЕННОЕ ГОСУДАРСТВО". 24 September 2015. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 12 April 2023.

- ^ "Журнальный зал | Знамя, 1996 N3 | Андрей Зубов - Будущее российского федерализма". 26 October 2013. Archived from the original on 26 October 2013. Retrieved 12 April 2023.

- ^ a b c d Kazansky, N.N. (2009). acta linguistica petropolitana (PDF) (in Russian). St. Petersburg: russian academy of sciences - institute for linguistic studies.

- ^ Chernin, Velvl (30 December 2023). "Kalmykia: Ethnic Separatism in the Lower Volga Region". Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ "Калмицька проблема для росії" [Kalmyk problem for Russia]. www.ukrinform.ua (in Ukrainian). 15 December 2022. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ "Степное Уложение (Конституция) Республики Калмыкия" [The Steppe Statute (Constitution) of the Republic of Kalmykia.]. glava.region08.ru. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ "Калмыцкое государство, Ногайская республика или "Поволжский Евросоюз"?". RFE/RL (in Russian). 17 November 2022. Archived from the original on 24 December 2022. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ ""Если бы существовал рейтинг регионов по демократичности, Калмыкия заняла бы одно из последних мест"". RFE/RL (in Russian). 20 July 2022. Archived from the original on 3 January 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ Узел, Кавказский. "Пацифистское заявление верховного ламы Калмыкии вызвало дискуссии в соцсетях". Кавказский Узел. Archived from the original on 7 October 2022. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ a b Chernin, Velvl (30 December 2023). "Kalmykia: Ethnic Separatism in the Lower Volga Region". Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ Бредихин, А.В. (2016). "Казачий сепаратизм на юге России". Казачество: 36–44. Archived from the original on 21 January 2023. Retrieved 21 January 2023.

- ^ "Как власти Краснодарского края поддерживают казачий сепаратизм". Красная весна (in Russian). 28 October 2017. Archived from the original on 3 January 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "В России провозгласили Кубанскую народную республику". POLITua (in Russian). 30 January 2018. Archived from the original on 13 October 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ a b Шхагапсоев, Заурби; Карданов, Руслан (2022). "ПРОБЛЕМА СЕПАРАТИЗМА В РОССИЙСКОЙ ФЕДЕРАЦИИ (НА ПРИМЕРЕ РЕГИОНОВ СЕВЕРНОГО КАВКАЗА)". Социально-политические науки. 12 (3): 83–84. doi:10.33693/2223-0092-2022-12-3-82-85. S2CID 252348427.

- ^ "«Сепаратизм порождается провокационной политикой Кремля»".(in Russian)

- ^ "UNPO: Circassia". unpo.org. Archived from the original on 26 January 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "Бацилла сепаратизма". Газета.Ru (in Russian). 26 November 2008. Archived from the original on 3 January 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "We Will Not Forget the Circassian Genocide!". hedep.org.tr (in Turkish). Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ Узнародов, Д.И. (2019). "ЧЕРКЕССКИЙ ВОПРОС НА ЮГЕ РОССИИ: ЭТНОПОЛИТИЧЕСКИЕ ИТОГИ И ПЕРСПЕКТИВЫ" (PDF). Caucasology (3): 222–236. doi:10.31143/2542-212X-2019-3-222-239. S2CID 211390612.

- ^ "HOME | The Council Of United Circassia". United Circassia. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ "Appeal to Antonio Guterres, United Nations Secretary General, from Council of United Cirsassia" (PDF). 2024. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 May 2024. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ "Mustafa Canbek's Speech on Kyiv Conference 2023". Archived from the original on 24 May 2024.

- ^ "Ichkeria recognized the Holodomor as genocide of the Ukrainian people". Uaposition. 28 November 2022. Archived from the original on 2 December 2022. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "Ukraine lawmakers brand Chechnya 'Russian-occupied' in dig at Kremlin". Reuters. 18 October 2022. Archived from the original on 11 December 2022. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ a b c "Рост сепаратизма на Северном Кавказе". www.kommersant.ru (in Russian). 9 September 1993. Archived from the original on 13 May 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ Гаджиев, Магомедэмин (2016). "Роль органов власти в разрешении межнациональных и межэтнических конфликтов в республике Дагестан". Вестник Пермского университета. Серия: Политология (2): 36–38.

- ^ "Суд освободил от уголовной ответственности экс-редактора "Фортанги" по делу о призывах к сепаратизму". ОВД-News (in Russian). Archived from the original on 3 January 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ Узел, Кавказский. "Провокация сепаратизмом". Кавказский Узел. Archived from the original on 15 December 2022. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ Узел, Кавказский. "Активизация вооруженного подполья в Ингушетии весной 2023 года". Кавказский Узел. Retrieved 12 April 2023.

- ^ Лагунина, Ирина (6 August 2008). "Почему все больше осетин не хотят быть россиянами". Радио Свобода (in Russian). Archived from the original on 15 December 2022. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ Мацаберидзе, Давид (2012). "РОЛЬ КОНФЕДЕРАЦИИ ГОРСКИХ НАРОДОВ В КОНФЛИКТЕ ВОКРУГ АБХАЗИИ". Кавказ и Глобализация. 6 (2): 44–54. Archived from the original on 15 December 2022. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "В Комитете ингушской независимости заявили, что не имеют отношения к проекту "Горской республики", представленной Закаевым". Новости Ингушетии Фортанга орг (in Russian). 21 March 2023. Retrieved 7 July 2023.

- ^ "Сепаратизм в Татарии и Башкирии | Намедни-1992". namednibook.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on 3 January 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "Уфа продолжает политику "тихого сепаратизма"". РБК (in Russian). 29 August 2002. Archived from the original on 3 January 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ a b "Башкорты и башкирцы". Регион.Эксперт (in Russian). Archived from the original on 3 January 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "В Башкирии тысячи человек вышли на протест против разработки на горе Куштау". Interfax.ru (in Russian). 16 August 2020. Archived from the original on 22 December 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "В Башкирии после призывов сепаратистов опять жгут поклонные кресты". EADaily (in Russian). 6 November 2020. Archived from the original on 3 January 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "Как пытаются раскачать Башкирию". www.stoletie.ru. Archived from the original on 3 January 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "В составе ВСУ появилось башкирское воинское подразделение". RFE/RL (in Russian). 2 December 2022. Archived from the original on 17 March 2023. Retrieved 12 April 2023.

- ^ a b "Собираются ли чуваши "на выход" из тюрьмы народов". www.depo.ua (in Russian). Archived from the original on 3 January 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "Тоской по суверенитету из Чувашии вдохновились на Украине". EADaily (in Russian). 19 January 2016. Archived from the original on 17 March 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "Почему РПЦ считает чувашское язычество сепаратизмом?". RFE/RL (in Russian). 25 August 2016. Archived from the original on 4 December 2020. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f "IV Форум свободных народов постРоссии проведут в шведском Хельсингборге — что известно". Freedom (in Russian). 25 November 2022. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ "Эрзянь Мастор". Свободный Идель-Урал (in Russian). 2 May 2019. Archived from the original on 3 January 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "Эрзянский национальный съезд заговорил о независимости для эрзян". RFE/RL (in Russian). October 2022. Archived from the original on 26 December 2022. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "Free Idel-Ural Movement takes shape in Kyiv". Euromaidan Press. 24 March 2018. Archived from the original on 3 January 2023. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ "Программа общественного движения "Свободный Идель-Урал"". Свободный Идель-Урал (in Russian). Archived from the original on 3 January 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "Когда развалится Россия: Почему Йошкар-Оле не нужна Москва – Последние новости мира". www.depo.ua (in Russian). Archived from the original on 3 January 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "Марийское язычество потеснит православную культуру". www.ng.ru. Archived from the original on 3 January 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ Makuhin, Fedor (14 May 2020). "Сепаратизм – спящий пёс Татарстана". Русская Планета. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ a b "РЕЗУЛЬТАТЫ РЕФЕРЕНДУМА РЕСПУБЛИКИ ТАТАРСТАН 21 марта 1992 года ПРОТОКОЛ Центральной комиссии референдума Республики Татарстан" (in Russian). 23 October 1999. Archived from the original on 23 October 1999. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "THE DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE OF TATARSTAN - CNN iReport". 30 March 2014. Archived from the original on 30 March 2014. Retrieved 5 July 2023.

- ^ "Татарский гамбит: почему Казань вновь вступила в противостояние с Москвой". NEWS.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on 3 January 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "Казань ответила Москве: Сепаратизм, ответ Путину, этнические обиды?". RFE/RL (in Russian). 17 July 2020. Archived from the original on 2 January 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ a b c "Почему удмурстким сепаратистам Будапешт ближе Москвы". www.depo.ua (in Russian). Archived from the original on 3 January 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "Финно-угры сочетают в себе глобальность и стремление к автономии". Регион.Эксперт (in Russian). Archived from the original on 3 January 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ ""Тут нет поводов говорить по-удмуртски". Из-за чего погиб ижевский ученый Альберт Разин". BBC News Русская служба (in Russian). Archived from the original on 3 January 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "Нет человека – нет проблемы?". Регион.Эксперт (in Russian). Archived from the original on 3 January 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ Штепа 2019, p. 55.

- ^ "Восстание российских регионов". Регион.Эксперт (in Russian). Archived from the original on 7 December 2022. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ ""Урал станет свободным, даже если Запад будет спасать Москву"". Регион.Эксперт (in Russian). Archived from the original on 8 December 2022. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "История сепаратизма: Уральская республика". hromadske.ua (in Russian). 26 September 2016. Archived from the original on 3 January 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ Штепа 2019, p. 95.

- ^ a b Сушко, А.В. (2018). "ИСТОРИЧЕСКИЕ ИДЕИ И ПОЛИТИЧЕСКИЕ ПРАКТИКИ СИБИРСКОГО СЕПАРАТИЗМА". Вестник Томского государственного университета (426): 192–206. doi:10.17223/15617793/426/23. eISSN 1561-803X. ISSN 1561-7793.

- ^ Штепа 2019, pp. 51–53.

- ^ a b Колоткин, Михаил; Сотникова, Елена (2021). "Сибирский сепаратизм в геополитическом пространстве России". Интерэкспо Гео-Сибирь: 36–38. doi:10.33764/2618-981X-2021-5-31-39.

- ^ Штепа 2019, pp. 101–102.

- ^ "Движение за федерализацию Сибири". BBC News Русская служба (in Russian). 31 July 2014. Archived from the original on 3 January 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.